Dementia presents a multifaceted challenge, profoundly influencing not only cognitive function but also an individual’s relationship with food and their overall well-being. Ensuring optimal nutritional care for those living with dementia is paramount, yet it often brings a unique set of complexities and questions. Following on from our recent webinar “Dementia and Nutritional Care: New Insights”, Alexandra Rees and Sophia Cornelius answer the top questions around dementia and nutrition from prevention of dementia to communication and social aspects.

By Alexandra Rees and Sophia Cornelius

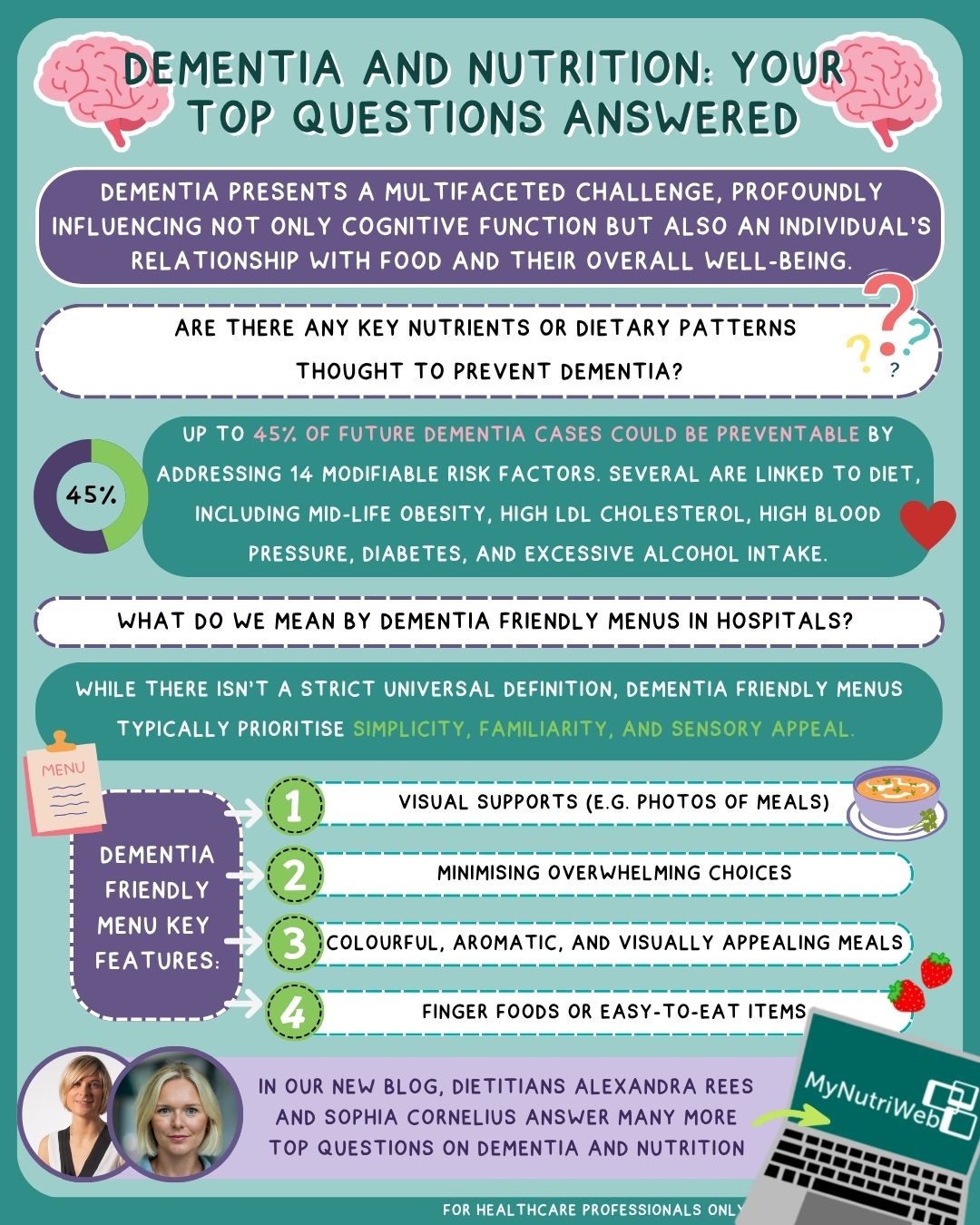

Are there any key nutrients or dietary patterns thought to help prevent dementia? 1,2,3,4,5,6,7

When we talk about brain health, it’s easy to think only about genetics or age – but in reality, lifestyle plays a far more powerful role than many of us realise. While some factors like age, sex, or genetics are outside our control, growing evidence suggests that certain modifiable lifestyle choices can significantly impact our risk of developing dementia.

In the 2024 Lancet Commission’s report there are 14 potentially modifiable risk factors – including lifestyle and environmental elements – that could help prevent up to 45% of future dementia cases. Of these, the following have a link to dietary intake:

- Mid-life obesity

- High LDL cholesterol

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Excessive alcohol consumption

Nutrition: shifting from nutrients to patterns – In the past, research had focused on individual nutrients like B vitamins, vitamin D, vitamin E, or omega-3 fatty acids. Yet, there’s still no strong evidence supporting the use of any single nutrient supplement to prevent dementia. Instead, the spotlight is shifting to overall dietary patterns, which appear to have more measurable benefits. Why? Because nutrients often work synergistically, their combined effects within a balanced diet may better support brain health than any one nutrient alone.

Current evidence points to three dietary patterns that could help reduce dementia risk:

- Mediterranean Diet: Rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, olive oil, fish, and poultry, this diet avoids saturated and trans fats and limits red meat and sugary foods.

- DASH Diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension): Originally designed to lower blood pressure, the DASH diet emphasises vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, and low-fat dairy, while minimising saturated fat and sugar.

- MIND Diet (Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay): This hybrid combines the best of both worlds. It calls for high intake of berries and leafy greens, along with nuts, legumes, olive oil, and whole grains, while restricting red meat, full-fat cheese, sweets, and fried foods.

The Bottom Line – There’s no magic bullet when it comes to preventing dementia. But by adopting a dietary pattern that is rich in whole foods (predominately plants with limited amounts of animal foods) and limiting intake of highly processed foods high in fats and sugars, we may be able to protect our longer term brain health.

Can we stop or reverse the cognitive decline with diet? 8

As of now, there’s no strong scientific evidence that any specific food or nutrient can stop or reverse the symptoms of dementia. So, what does the evidence support? The answer lies in preventing malnutrition and frailty. For individuals living with dementia, maintaining physical health and independence is crucial.

Malnutrition can sneak in quietly, especially as dementia progresses. Difficulty with eating and drinking may arise, creating a vicious cycle – malnutrition can worsen dementia, which then makes eating and drinking more difficult, further compounding the risk.

The key to breaking this cycle? A diet that is varied and balanced that includes:

- Plenty of energy-rich whole foods

- High-quality protein sources

- Essential vitamins and minerals like:

- Calcium, Vitamin D, Vitamin B12, Vitamin C. Folate

A varied dietary pattern rich in whole foods will help support overall physical health, muscle maintenance, and immune function – all crucial for people living with dementia.

Final thought: While no nutrient is a cure, thoughtful dietary support is powerful. It won’t reverse dementia, but it can help preserve quality of life, prevent physical deterioration, and promote independence longer.

Are there any nutritional supplements recommended for patients with dementia? 8,9

When it comes to maintaining health and well-being, especially in vulnerable populations, nutrition plays a vital role. For individuals who struggle to meet their nutritional needs through regular food intake – including those living with dementia – oral nutritional supplements (ONS) might be beneficial.

These supplements contain concentrated doses of energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Their purpose? To help prevent or alleviate malnutrition, which can lead to a range of serious health consequences.

According to recent research (Volkert et al., 2024), there’s currently no strong or consistent evidence that oral nutritional supplements can prevent or delay cognitive decline associated with dementia. Oral nutritional supplements can however be a useful tool to prevent malnutrition where sufficient dietary intake is not possible to meet their nutritional needs.

What is the latest evidence about nutrition support for care home residents living with dementia? 8

Nutrition is far more than just what’s on the plate – especially for care home residents living with dementia. As our understanding deepens, it’s clear that thoughtful, person-centred nutritional care can significantly enhance quality of life, preserve independence, and support physical and cognitive health.

Every resident deserves a tailored, nutritional care plan that reflects their:

- Individual preferences

- Cultural and religious beliefs

- Physical capabilities (e.g., ability to chew, swallow, self-feed)

Menus should evolve with the seasons to stay fresh and appealing – and care homes must be equipped with enough staff to offer meaningful mealtime support, especially to those with dementia.

Relationship-Centred Nutrition:

This means placing the person living with dementia at the core of their nutritional care and honouring:

- Their personal life story and past food habits

- Their relationship with family and caregivers

- Their individual behaviours around eating and drinking

Tools like life story documents can bridge communication gaps and build deeper understanding – ensuring nutrition is not just clinical, but deeply personal.

Creating Mealtime Experiences That Matter:

The environment matters as much as the meal itself. Care homes should:

- Serve meals in functional, welcoming dining rooms

- Create an atmosphere that encourages appetite and social engagement

- Promote communal eating to nurture connection and improve mealtime enjoyment and mirror a typical, family dining environment

- Well lit environments

Fortifying Food with Purpose:

Food fortification should never be one-size-fits-all. Instead, it should be:

- Based on a varied, balanced, and individualised diet

- Integrated into a comprehensive strategy that meets energy, protein, and micronutrient needs

- Sensitive to the person’s tastes and abilities

Choices That Empower:

Care organisations should offer:

- Attractive and nutritious meals, snacks, and drinks

- Enough variety to avoid boredom and support adequate intake

- Opportunities for residents to choose what – and how – they eat and drink

Resources to Support Best Practice:

The Care Home Digest, developed by the BDA Older People Specialist Group, the BDA Food Services Specialist Group, and the National Association of Care Caterers, offers guidance on supporting nutritional needs in care homes. A dedicated section focuses on dementia-specific strategies. Care Home Digest – BDA

What are the ethical considerations of naso-gastric (NG) feeding in acute illness with dementia?8,10

Nasogastric (NG) feeding in people living with dementia – particularly during acute illness – is a delicate, often emotionally charged decision. It’s not simply about delivering nutrition; it’s about respecting dignity, autonomy, and quality of life. Decisions surrounding NG feeding should always be made on a case-by-case basis, considering both clinical realities and human values.

Start with the individual: Every person is unique, and so should be their care. Decisions around NG feeding must weigh

- The person’s clinical presentation and general prognosis

- The intended outcome of NG feeding

- Any known preferences or previous feelings expressed by the individual

For those with dementia, communication challenges can make these conversations more complex – but it’s crucial not to assume lack of capacity. Where possible, individuals should be supported in expressing their wishes.

Balancing Benefit and Burden: Ethical principles like beneficence (doing good) and non-maleficence (avoiding harm) guide us to ask tough questions:

- Will NG feeding prolong meaningful life – or prolong suffering?

- Can it help maintain independence and physical function?

- Are the therapeutic goals realistic, given the person’s condition?

Only when a clinical indication exists and the expected outcomes are compassionate and achievable should NG feeding be considered.

Honouring Autonomy and Personal Values: Respect for autonomy means involving the individual, their family, and the broader care team in open, honest discussions. This includes:

- Considering advance directives or living wills

- Consulting with proxies or legally appointed decision-makers

- Understanding values, culture, and spiritual beliefs that influence decision-making

- In late-stage dementia, when informed consent may not be possible, previously expressed preferences become especially important.

Food and hydration carry emotional and cultural significance – sometimes more than clinical value. Families may see it as a form of care and connection. These views deserve empathy and dialogue, not dismissal.

When uncertainty reigns, a time-limited trial of NG feeding may help evaluate its impact. At the same time:

- Thoughtful hand-feeding can offer comfort and dignity

- Skilled palliative care can address discomfort and promote peace

- Ethics committees can provide valuable support in complex cases

Final Thoughts: NICE Guideline NG97 (2018) also states that enteral feeding should not be considered for people living with advanced dementia unless indicated for a potentially reversible co morbidity NG feeding is never a simple yes-or-no decision – it’s a journey through medical facts, ethical considerations, and human values. With compassion, clarity, and collaboration, care teams can uphold dignity and support informed choices, even in the hardest moments.

With budget, time and ingredients constraints, what advice would you give to nursing home chefs to adopt the food first approach?

To best cater for complex nutritional needs when short on time, ingredients and money, it is essential that chefs know their residents well. Ideally, the core menu should be able to cater to the majority of nutritional needs – such as gluten-free, easy chew, energy-dense, and higher-protein meals. A la carte options should be reserved for more complex dietary requirements where the risk of getting it wrong is higher (e.g. texture-modified diets and allergens). Chefs can be strategic in making one dish adaptable for various needs by fortifying individual components (e.g. adding milk powder, cream, cheese, or butter) to boost nutritional density with minimal impact on preparation time or flavour. Batch cooking and thoughtful menu rotation can also help reduce waste and save time, while still prioritising nutrient-rich options.

Do you have any tips for improving food intake in those who lose their taste and smell?

As we age, changes to taste and smell are common – whether due to the natural ageing process, medications, or illness. Foods that were once favourites may now seem bland, reducing mealtime enjoyment. Encourage residents to explore new and more flavourful options – spicy, sweet, bitter, or umami-rich foods may be more appealing than familiar dishes. Introducing new cuisines, using herbs, spices, citrus, and flavour-enhancing condiments can add interest and improve intake. Texture contrast (e.g. crunchy toppings on soft meals) can also enhance the overall eating experience.

Lots of clients have very small appetites, we leave chopped fruits out for in between visits, do you have any other suggestions?

Fruit is an excellent source of fibre and vitamins but tends to be low in calories and protein. For nutritionally vulnerable individuals, it’s important to combine fruit with something more nutrient-dense – such as nut butters, Greek yoghurt, or cheese – to help boost overall energy and protein intake. In addition to fruit, consider offering small, nutrient-dense finger foods that are easy to eat and appealing. Examples include cheese cubes, with or without a cracker or biscuit, nut butter on toast fingers, savoury scones, boiled egg halves or even biscuits or cake. Smoothies, milkshakes, and fortified drinks (like milk with added skimmed milk powder) can be left for sipping between meals, consider leaving in a thermos to maintain freshness if your clients drink slowly. Timing is important too – we don’t want people filling up on fluids or snacks before their main meals, so ensure adequate time is left between snacks and meals to promote hunger and maximise intake.

Considering palatability, price and nutrition, what is the number one ingredient you would recommend for food fortification?

Skimmed milk powder is a top choice. It’s cost-effective, readily available, and highly versatile. It can be mixed into milk to boost its protein and calorie content, stirred into mashed potatoes, porridge, soups, or sauces, and used in baking. It blends easily and has a neutral taste, making it ideal for fortifying without affecting meal enjoyment. For those not liking or wanting skimmed milk, following a vegan diet or with a milk allergy, there are alternatives. Nutritional yeast is an excellent alternative. It’s rich in protein, often fortified with B12, and adds a savoury, cheese-like flavour to foods. While slightly more expensive per gram than skimmed milk powder, its strong nutritional profile and unique umami taste make even small amounts effective. Nutritional yeast can be sprinkled over pasta, stirred into soups or mashed potatoes, blended into sauces, or added to baking for a nutrient and flavour boost. It’s widely available in UK supermarkets and health stores, and its long shelf life and versatility make it a smart fortification option for plant-based diets.’ Nut butters are another ingredient often used for fortification for those following a vegan diet depending on patient preference and dietary requirements.

Is there a definition of what we mean by dementia friendly menus in hospitals?

While there isn’t a strict universal definition, dementia-friendly menus typically prioritise simplicity, familiarity, and sensory appeal. Key features include:

- Clearly named, recognisable dishes that are easy to understand.

- Visual supports (e.g. photos of meals) to aid in decision-making.

- Minimising overwhelming choices – offering fewer but well-considered options.

- Finger foods or easy-to-eat items for those with motor or cognitive challenges.

- Meals that are colourful, aromatic, and visually appealing to stimulate appetite.

- Consideration of routine and consistency to reduce confusion around mealtimes.

Blog Infographic Summary:

References

- Aridi, Y., Walker, J, Wright, O. The Association between the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Cognitive Health: A Systematic Review, Nutrients 2017 (9); doi: 10.3390/nu9070674

- Ye, K et al. The role of lifestyle factors in cognitive health and dementia in oldest-old: A systematic review, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2023: 152 105286

- Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet. 2024 Aug 10;404(10452):572-628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0. Epub 2024 Jul 31. PMID: 39096926.

- Bermejo-Pareja, F. et al. Is milk and dairy intake a preventative factor for elderly cognition (dementia & Alzheimer’s): A quality review of cohort surveys, Nutrition Reviews 2020, 79 (7): 743-775

- Castro et al. Multi-Domain Interventions for Dementia Prevention- A Systematic Review (2023) J Nutr Health Aging 27(12):1271-1280

- Limongi, F et al., The Effect of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet on Late-Life Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review, JAMDA, 2020: 1402-1409

- van den Brink, A., Brouwer-Brolsma, E., Berendsen, A., & van de Rest, O. The Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diets Are Associated with Less Cognitive Decline and a Lower Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease—A Review Adv Nutr 2019;10:1040–1065; doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz054.

- Volkert et al.- ESPEN guidelines on nutrition and hydration in dementia-Update 2024, Clinical Nutrition 2024; 43:1599-1626

- Cesari et al. Nutritional intervention for early dementia. (2021) Journal of Nutrition & Healthy Aging 25 (5) 688-691

- Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers NICE guideline [NG97] Published date: June 2018.