Dr Holly Neill – Holly is the Science Officer at Yakult UK and Ireland where she communicates the latest research on the gut microbiota, probiotics, and health. Before moving to industry, she worked as a postdoctoral researcher and has published her research in high impact journals alongside presenting at both national and international conferences.

Dr Emily Prpa – Emily is an award-winning registered nutritionist and the Science Manager at Yakult UK and Ireland, with a PhD in Nutritional Sciences from King’s College London. Her research has been presented internationally and helped inform UK Food Policy. She is considered one of the leading experts in her field and is frequently featured in the media, including the BBC and Sky News.

Research into the gut microbiome has exponentially increased over the past decade. We are now uncovering how the gut microbiome plays a vital role in overall health – going far beyond merely digestion – and can influence the development of certain conditions.

This heightened interest and appreciation for the gut microbiome in relation to health and wellbeing has extended beyond the scientific community and rapidly captured the attention of the “worried well”. The concern for gut microbiome health has led to the commercialisation of at-home test kits.

Once a specialised measurement confined to clinical and research settings, gut microbiome testing is now readily available to everyday consumers. These tests offer a glimpse into the complex ecosystem residing within part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. But what do they actually measure, and do they live up to the hype?

What is the gut microbiome?

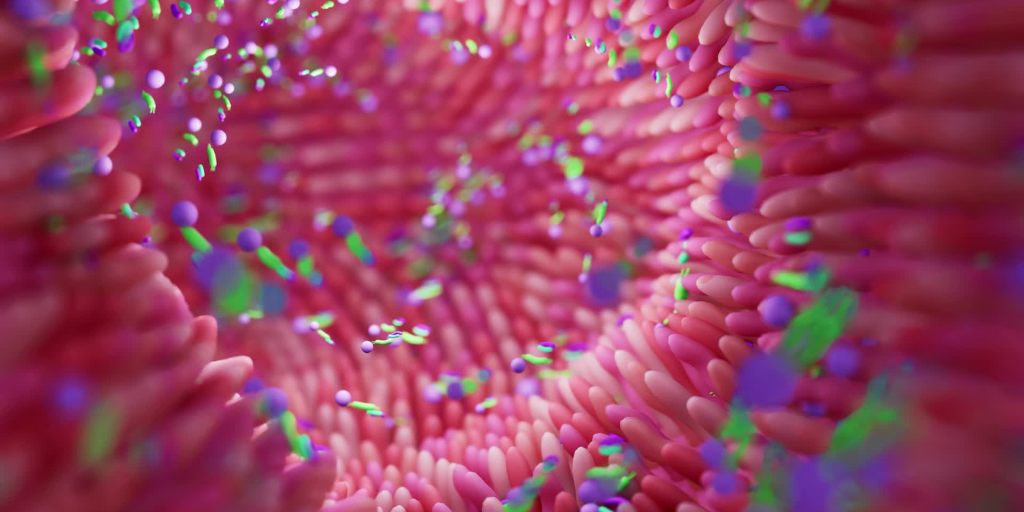

The gut microbiome refers to the fascinating ecosystem residing within our digestive tract – the microbes (e.g. bacteria, yeasts, viruses, phages, archaea, fungi and parasites), along with their collective genetic material and the metabolites they produce (e.g. vitamins and short-chain fatty acids, SCFAs).

Nowadays, the term “gut health” often appears to be synonymous with a “healthy gut microbiome”. However, while “gut health” is defined as “the absence of GI symptoms and disease1, there is no universally accepted profile for a “healthy” gut microbiome. This is due to the large inter- and intra-variability that exists, and the many unique combinations of thousands of different microbial species which can reside within the gut microbiome. Instead, in research, a gut microbiome is considered optimal when it is diverse, stable and resilient.2

What do microbiome tests measure?

Microbiome tests examine the gut microbiome composition using an individual’s stool sample. Depending on the method used, results can reveal which micro-organisms are currently present within the colon (i.e. bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea). Individuals usually provide the sample at home and then post it, either on a one-off occasion or as part of a subscription.

Put simply, a gut microbiome test can reveal the different types of microorganisms present in an individual’s colon (i.e. the last part of the GI tract).

There are two main analytical methods for gut microbiome tests: 16S rRNA sequencing and deep shotgun genome sequencing.

16S rRNA sequencing is an older analytical approach with limitations as it focuses on only one specific gene within DNA to identify bacteria. Therefore, it can only provide an indication of the bacteria present at the genus level, rarely at the species level, and does not provide strain details. This test is also not able to detect all microbes, particularly those in small quantities. By failing to capture the entirety of microbes present, crucial microbial details could be lacking.3

Deep shotgun sequencing is a more advanced technique which identifies all DNA present (even those in smaller quantities), possibly providing strain level details and in silico reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genome data (MAGs). In most cases, only one individual sample is run at a time which is reflected in the much higher cost. Shotgun sequencing can provide enormous amounts of impressive data regarding the entire metagenome, reflecting not only the composition of the sample, but also its metabolic potential (e.g., production of vitamin B or K in the gut). Data analysis requires, however, sophisticated bioinformatics tools and databases, managed by experienced staff. Moreover, there is still a lack of knowledge regarding the biological understanding of such data and its relevance to healthy individuals and/or disease risk.

Why is there an interest in gut microbiome tests?

Gut microbiome tests have traditionally been used within clinical settings, for specific patients. For example, when there has been a severe disturbance to the balance of microbiota due to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), or lifelong antibiotics treatment.4-6 In such cases, the gut microbiota composition can be measured at baseline and then measured again following a dietary intervention, to identify general improvements.

In research settings, gut microbiome tests are being used to advance our understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in disease risk, development and treatment – showcasing the potential for the gut microbiome to be a powerful new tool in modern medicine. For example, associations between gut microbial composition and conditions such as colon cancer,7 depression8 and obesity9 (amongst many others) have been observed. Most recently, the balance and ratio of specific bacterial communities in the gut have been shown to help predict who will respond to next-generation drugs for treating certain types of cancers.10

Therefore, it is important to highlight that the concept itself is not considered “new” but rather the commercialisation of such tests, now offered to the general, healthy, population. Recently, interest in gut microbiome testing has grown significantly as the gut microbiota is now well-recognised as “the conductor of health”; the gut microbiota is orchestrating organs and systems in the human body to maintain homeostasis – and, as such, providing a potential avenue to improve health through nutrition. This, together with an ever-growing excitement for personalised nutrition, has opened the doors for a multitude of commercial at-home gut microbiome tests.

Is it worth the hype?

- Gut microbiome tests can detect the names of microbes present (i.e. at the genus level) such as Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus and Enterococcus but, depending on the analytical technique, cannot always identify strains or explain functionality of the microbes. Essentially, microbiome tests based on 16S rRNA sequencing analysis can inform “who is there” but not exactly “what they do”. Deep shotgun sequencing does have this potential, but biological interpretation remains challenging.

- How microbes collectively act within the microbiota depends on the entire environment and other microbes present. While a real pathogen can obviously be detected and warned for, based only on the results of a gut microbiome test, defining a single “good” or “bad” bacteria in terms of metabolic or immune performance is complicated, as it is the total ecosystem composition which will determine whether a specific bacterium is favourable or not to the host. Due to the intense complexity of the gut microbiota, and it being unique to each person, it is not always clear at the moment what interventions would be best on the basis of test results, as the ecosystem is extremely complicated, with still many unknowns11. It remains therefore extremely difficult, almost impossible, to predict which specific dietary intervention would create a “healthier” microbiota than the microbiota composition an individual currently has.

- Unlike many other tests, reference values do not exist. Therefore, clinicians are often unable to offer any specific guidance to already healthy patients when presented with gut microbiome test results which do not currently provide value to clinical decisions.12

- Gut microbiome tests are generally a single measure at a single timepoint. Repeated testing would permit monitoring of the evolution of the microbiota composition during a specific period (e.g. during an intervention period or pregnancy etc) and may allow to monitor the result of an intervention or initiate conclusions regarding long-term impacts, but can be difficult due to the high cost.

- Measuring a stool sample only captures microbes present in the last part of the GI tract (i.e. the colon). However, the gut microbiome exists throughout the entire GI system, and these tests do not detect any microbial profile further up the ~9m long GI tract.

What does the future hold for gut microbiome testing?

Everyone is unique and therefore a personalised approach to health and nutrition, based on individual genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, holds great potential, argubly more effective than a generic approach.13 However, it has been argued that further research and advancement in analytical techniques, we well as our understanding/interpretation of results, are required before personalisation can deliver such desired results. As technology further advances and biological understanding increases, commercialisation of gut microbiome testing can provide insights into overall health, potential gut imbalances and predisposition to various unfavourable conditions. This will equip healthcare providers with a powerful tool to offer personalised advice and interventions.

Spend smart: 3 key considerations for gut microbiome testing

- Ensure access to specialist support from a trained healthcare professional such as a Registered Nutritionist or Dietitian who is able to help interpret the results.

- Have realistic expectations about the information the test can provide e.g. it is unable to identify or diagnose certain unfavourable conditions; it will not always capture the whole microbial community (depending on analytical method used); it often does not provide functionality of the gut microbiome (depending on the test type again) which is more important than only knowledge of the compositional data.

- Be aware of the total cost from single or subscription testing. Could money spent on an expensive gut microbiome test be used elsewhere e.g. purchasing more fruit and vegetables, buying a gym membership or subscribing to a new mindfulness app? All these habits are known to directly or indirectly support the gut microbiome.

How can we support our gut microbiome?

Arguably, motivation to use a commercial gut microbiome test is fuelled by the goal of optimising gut health. Eager to enhance physical and mental wellbeing, people can often overlook or neglect basic fundamentals in favour of these costly tests. At Yakult Science for Health, we have developed the five pillars which can optimise gut health, confirmed continuously by the latest scientific research:

1, Diet: The gut microbiota changes according to the foods we eat.1 Consuming a high fibre diet with a variety of plants, ‘feeds’ and increases the number and types of beneficial bacteria residing in the gut (e.g. lactobacilli and bifidobacteria). Research shows those who eat >30 different types of plants per week have a more diverse gut microbiome compared to those who eat <10 plants.15

2. Exercise: Regular exercise increases the diversity of the gut microbiota and increases the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut, both of which can reduce inflammation and support immune function.16 Exercise also improves mucosal barrier function and stimulates production of SCFAs (e.g., butyrate, propionate) which can protect against GI disorders.17

3. Sleep: Irregular sleep patterns are associated with poorer diet quality, inflammation, and reduced gut microbiota diversity.18

4. Hydration: Hydration is important for digestion and overall gut health.19

5. Mindfulness: There is a close link between the brain and the gut. Mindfulness has been associated with improved physical, mental, and gut health. It can alter the gut microbiota composition in such a way that it could help to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression.20

Take home message

Undoubtedly, the concept of gut microbiome testing is incredibly exciting and holds significant promise. As research continues in this area, such testing could prove a powerful avenue for realising the possibilities of improving health through nutritional interventions by targeting gut microbiota deficiencies – revolutionising patient care and making gut health a cornerstone of modern medicine.

But has public interest is moved faster than science? Commercial gut microbiome tests are in their infancy and currently the evidence is limited for their benefit to the general public. Previously their applications were restricted to clinical practice, in treating patients with clear disturbances to their gut microbiome as a result of certain medical conditions. Therefore, results can be of interest to those curious to know which microbes are present at the lower end of the GI tract but, at this stage, functionality is not fully understood, and individual results cannot, with certainty, be linked to disease risks.

Despite the surge in these expensive tests, promising health empowerment, the real gut health game-changers – emphasised even in the latest and most ground-breaking research – lie in the basics: a diverse diet, regular exercise, good quality sleep, adequate hydration, and minimising stress. Gut tests can offer intriguing, albeit sometimes limited insights; however, it is the everyday lifestyle choices that hold the power to transform health from the inside out.

To keep up-to-date with the latest resources, news and events from Yakult Science for Health, sign up to their newsletter here or follow them on social media (LinkedIn and Instagram).

Written in collaboration with Yakult Science for Health

Disclaimer: This blog has been written in collaboration with the nutrition team at Yakult Science for Health and reviewed by the MyNutriWeb nutrition and dietetic team. Approval of each sponsor and activity is carefully assessed for suitability on a case by case basis. Sponsorship does not imply any endorsement of the brand by MyNutriWeb, its organisers, its moderators or any participating healthcare professional, or their association. Sponsorship funds are reinvested into the creation and promotion of professional development opportunities on MyNutriWeb.

References

- Staudacher HM, Loughman A. Gut health: definitions and determinants. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(4):269. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00071-6.

- Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489(7415):220-230. doi:10.1038/nature11550.

- Thomas AM, Segata N. Multiple levels of the unknown in microbiome research. BMC Biol. 2019;17(1):48. doi:10.1186/s12915-019-0667-z.

- Banaszak M, Górna I, Woźniak D, Przysławski J, Drzymała-Czyż S. Association between Gut Dysbiosis and the Occurrence of SIBO, LIBO, SIFO and IMO. Microorganisms. 2023;11(3):573. Published 2023 Feb 24. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11030573.

- Santana PT, Rosas SLB, Ribeiro BE, Marinho Y, de Souza HSP. Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenic Role and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3464. Published 2022 Mar 23. doi:10.3390/ijms23073464.

- Patangia DV, Anthony Ryan C, Dempsey E, Paul Ross R, Stanton C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen. 2022;11(1):e1260. doi:10.1002/mbo3.1260.

- Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(11):690-704. doi:10.1038/s41575-019-0209-8.

- Radjabzadeh D, Bosch JA, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Gut microbiome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7128. Published 2022 Dec 6. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34502-3.

- Alili R, Belda E, Fabre O, Pelloux V, Giordano N, Legrand R, Bel Lassen P, Swartz TD, Zucker J-D, Clément K. Characterization of the gut microbiota in individuals with overweight or obesity during a real-world weight loss dietary program: a focus on the bacteroides 2 enterotype. Biomedicines. 2022;10(1):16. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10010016.

- Guglielmi G. Gut microbiome discovery provides roadmap for life-saving cancer therapies. Nature. Published online June 20, 2024. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-02070-9.

- Hill C. You have the microbiome you deserve. Gut Microbiome. 2020;1:e3. doi:10.1017/gmb.2020.3.

- Staley C, Kaiser T, Khoruts A. Clinician guide to microbiome testing. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(12):3167-3177. doi:10.1007/s10620-018-5299-6.

- Ordovas JM, Ferguson LR, Tai ES, Mathers JC. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;361:bmj.k2173. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2173.

- De Angelis M, Garruti G, Minervini F, Bonfrate L, Portincasa P, Gobbetti M. The food-gut human axis: the effects of diet on gut microbiota and metabolome. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(19):3567-3583. doi:10.2174/0929867324666170428103848.

- McDonald D, Hyde E, Debelius JW, et al. American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. mSystems. 2018;3(3):e00031-18. Published 2018 May 15. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00031-18.

- Monda V, Villano I, Messina A, et al. Exercise modifies the gut microbiota with positive health effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3831972. doi:10.1155/2017/3831972.

- Wegierska AE, Charitos IA, Topi S, Potenza MA, Montagnani M, Santacroce L. The connection between physical exercise and gut microbiota: implications for competitive sports athletes. Sports Med. 2022;52(10):2355-2369. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01696-x.

- Bermingham KM, Stensrud S, Asnicar F, et al. Exploring the relationship between social jetlag with gut microbial composition, diet and cardiometabolic health, in the ZOE PREDICT 1 cohort. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62(8):3135-3147. doi:10.1007/s00394-023-03204-x.

- Popkin BM, D’Anci KE, Rosenberg IH. Water, hydration, and health. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(8):439-458. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x.

- Zhang D, Lee EKP, Mak ECW, Ho CY, Wong SYS. Mindfulness-based interventions: an overall review. Br Med Bull. 2021;138(1):41-57. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldab005.

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN:

Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: A Deep Dive

I learned so much from this article. It’s great to see gut health being highlighted as part of a healthy lifestyle!

Great read! Maintaining gut health is so important for overall well-being, and I appreciate the helpful insights shared in this post. Looking forward to learning more tips and advice on this topic!