Juliette Kellow, Registered Dietitian and member of the British Dietetic Association. Follow her on Instagram.

A staggering nine out of 10 people living with obesity say they’ve been stigmatised, criticised or abused because of their weight. But where is this behaviour coming from, how does it affect patients/clients and what can we do to stamp it out? With World Obesity Day on 4 March themed ‘Everybody needs to act’, Registered Dietitian Juliette Kellow investigates… We’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences: leave a comment in the box below.

Weight stigma, weight bias, weight discrimination! They’ve been experienced by many of our patients and clients for decades, but it’s only recently that steps have started to be taken to stamp them out. In the past few years, everyone from politicians and policy makers to health professionals and educators have started to recognise and understand the need to eliminate stigma and discrimination against people because of their weight.

While the terms weight bias, stigma and discrimination are often used interchangeably, they do have different meanings:

- Weight bias is defined as negative attitudes towards, and beliefs about, others because of their weight. This bias can be:

- Explicit or conscious, where a person recognises they have negative attitudes towards people living with obesity, or

- Implicit or unconscious, where a person is unaware of their attitudes: they say they’re not biased but without realising they treat or talk about a person living with obesity differently than they do about a person with a lower body weight.

- Weight stigma refers to social stereotypes and misconceptions about people based on their weight, for example, thinking people living with obesity are lazy or lack willpower. This stigma can also be internalised by people living with obesity, where they recognise and start applying these negative stereotypes to themselves, resulting in self-blame and criticism.

- Weight discrimination refers to discriminating behaviour towards people living with obesity, where people treat individuals unfairly because of their weight or size.

This bias, stigma and discrimination affects millions of people in many countries. It’s found across different ethnic, income and education groups, is experienced by men and women, and is seen in children, teenagers and adults. It can occur across the whole weight spectrum, including people who are underweight or with a normal weight, but it’s most commonly experienced by those with a higher weight.

The scale of the problem

With 64% of adults in England having a BMI over 25, many people face weight stigma. In a report from the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Obesity, 88% of people living with obesity said they’d been stigmatised because of their weight. Indeed, it’s now the biggest form of discrimination in the UK. In a poll conducted by the World Obesity Federation for World Obesity Day in 2018, 62% of Brits agreed someone who was overweight was likely to be discriminated against – higher than other forms of discrimination, including ethnicity (60%), sexual orientation (56%) and gender (40%).

Weight stigma is so deeply entrenched in our society it’s impossible to escape. Media is a big contributor, but it’s also seen in social situations, schools and colleges and in the workplace. In a study of more than 2,400 American women, 72% said they’d experienced weight stigma from family, 64% from classmates, 60% from friends, 54% from colleagues, 43% from employers, 32% from teachers and 23% from people in authority such as police.

Worryingly, stigmatising attitudes are also found extensively in healthcare settings – the very places where people living with obesity go to seek help. In the same study, doctors were the second most common source of weight stigma, with 69% of women saying they’d experienced this. Additionally, 46% reported weight stigma from nurses, 37% from dietitians and 21% from mental health professionals.

Meanwhile, even UK health policies and campaigns have been criticised for having stigmatising attitudes. It’s led to organisations such as the British Dietetic Association (BDA) requesting that weight stigma is avoided in any government communications and strategy focussed on obesity.

Consequences of weight stigma

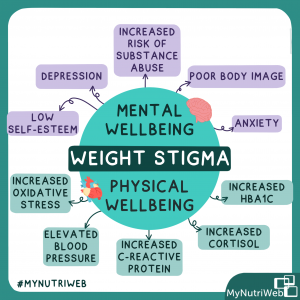

Numerous studies show stigmatising attitudes hinder rather than help people achieve better health. One study even found people who experience weight stigma have a 60% increased risk of premature death, independently of their BMI. Research shows weight stigma affects mental wellbeing, resulting in lower self-esteem, depression, anxiety, poor body image and an increased risk of substance abuse. It also affects physical wellbeing and is associated with elevated blood pressure and increased levels of C-reactive protein, cortisol, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and oxidative stress. These effects appear independent of BMI, suggesting stigma is the main risk factor rather than body weight.

One theory suggests stress has a large part to play in this. The Cyclic Obesity Weight-Based Stigma or COBWEBS model, proposes that weight stigma leads to stress, which increases cortisol levels and eating, leading to weight gain and obesity. Indeed, one study found cortisol concentrations in hair – a marker of chronic stress – were 33% higher in those who’d experienced weight discrimination compared with those who’d not. Meanwhile, a recent meta-analysis of 54 studies found weight stigma increased the risk of unhealthy behaviours and decreased the risk of healthy ones.

In particular, weight stigma seems to affect eating habits and activity levels in a direction that results in weight gain rather than weight loss. One study found over a four-year period, there was an increase in weight and waist circumference in those who experienced weight stigma compared to those who didn’t. In addition, the chances of developing obesity increased more than 6-fold in those with a normal or overweight BMI at baseline but reported stigma.

It’s perhaps unsurprising as weight stigma has been linked to binge eating, disordered eating patterns, unhealthy weight control and increased calorie intakes. Eating is a common response to experiencing weight stigma, named by 79% of people with obesity in one study – exceeding the 63% of people who turned to dieting. In another study, women who perceived themselves to be overweight consumed more calories and felt less in control over eating when exposed to a weight stigmatising news story compared with a non-stigmatising story. This wasn’t seen in women who didn’t perceive themselves to be overweight, indicating self-perceptions of body size, rather than actual body size may have a greater impact on responses to stigma.

Meanwhile, weight stigma has been linked to lower levels of activity. A study of adults aged 50 and over found perceived weight discrimination was linked to almost 60% higher odds of being inactive and 30% lower odds of taking part in moderate or vigorous activity at least once a week.

In short, weight stigma doesn’t encourage people to lose weight. Instead, it’s more likely to push people towards behaviours that promote weight gain and hinder weight loss. But this isn’t the only way weight stigma affects health. There’s now mounting evidence it affects the access to, and quality of, healthcare.

Weight stigma in healthcare settings

Although healthcare settings are meant to be a safe space where people can talk openly about their health and not feel judged, weight bias, stigma and discrimination is widespread. Negative attitudes and stereotypes towards people living with obesity have been documented amongst doctors, nurses, dietitians, psychologists, gynaecologists, professionals treating eating disorders, and even those dedicated to helping people living with obesity such as bariatric specialists.

Stereotypes that have been identified include views that patients with obesity are non-compliant, lazy, lacking in self-control, awkward, weak-willed, sloppy, unsuccessful, unintelligent and dishonest. This stigma also seems to be present before healthcare professionals even start working with patients – medical, dietetic, nursing and psychology students have all been shown to express bias. While some of this is explicit, much of the bias expressed by healthcare professionals towards patients with obesity is implicit. Both impact greatly on patients.

People living with obesity have reported feeling embarrassed and judged by healthcare providers because of their weight, are upset by comments made, feel there is a lack of empathy and respect, don’t feel they are taken seriously and say all their problems are blamed on their weight. In a UK report, only 26% of people said they’ve been treated with dignity and respect by healthcare professionals when seeking advice or treatment for obesity, while 42% didn’t feel comfortable talking to their GP about their weight.

Indeed, compared with people of a lower weight, healthcare providers have been found to spend less time in appointments, have less discussion, undertake fewer interventions and have less rapport with those of a heavier weight. There’s also the added embarrassment of being weighed, medical equipment being too small and insufficient comfortable seating in waiting or consultation rooms.

The outcome: patients have less trust in their healthcare providers, are less likely to stick with treatments, and are more likely to delay or avoid future appointments, examinations or screening for cancer or other illnesses.

What’s being done to reduce weight stigma?

Thanks to growing research providing evidence that weight stigma worsens the health of people living with obesity, the topic is now receiving a much greater focus. Experts agree change is needed at every level, with government and policy makers ensuring stigmatising content in obesity strategies is avoided through to individuals addressing their own biases.

Progress is certainly being made. On a global level, in 2016 the World Health Organization (WHO) set out an agenda for zero discrimination in healthcare. This was followed by a document for the WHO European Region that identified how Member States could address weight bias and obesity stigma.

In 2018, World Obesity Day focussed on eliminating weight stigma and extended its range of resources.

In 2019, there was a new Lancet nutrition initiative with a call for papers to contribute to the evidence base needed to reduce and eradicate weight stigma.

Momentum gathered in 2020 with the publication of The Joint International Consensus Statement for Ending Stigma of Obesity. Co-authored by world experts, the document included recommendations and a pledge to eliminate weight stigma, which has been signed by more than 100 medical and scientific societies, including the BDA, Diabetes UK and Obesity UK. Also in 2020, Obesity Canada – a Canadian charity that focusses on obesity research, education and advocacy – launched Clinical Practice Guidelines, which included a chapter on reducing weight stigma.

Although there is still much to do, the last few years have seen many positive steps in the UK. Some examples including:

- One of the five recommendations made in the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Obesity report was that ‘Obesity/weight management training should be introduced into medical school syllabuses to ensure GPs and other healthcare practitioners feel able and comfortable to raise and discuss a person’s weight, without any stigma or discrimination’.

- The BDA has introduced guidelines to ensure all content it creates avoids stigmatising people living with obesity. These can be viewed by BDA members.

- Weight stigma is increasingly becoming a key topic in events aimed at health professionals. For example, The Association for the Study of Obesity and Food Active! held webinars in 2021 on eliminating weight stigma, while The Dietitian Café held a podcast in 2022 on weight stigma in dietetics with expert views from Anne Wright RD and Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Leeds Dr Stuart Flint.

- In a report focussing on obesity from the British Psychological Society, a chapter was dedicated to reducing weight stigma.

- There’s a module on avoiding weight stigma in the Healthy Weight Coach programme – an initiative funded by Government to train primary healthcare professionals to help people achieve a healthier weight.

- The Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia (SOBA UK) has published consent guidance for patients with obesity that emphasises using people first language and avoiding ‘fat shaming’.

- The voice of patients with obesity is becoming a core part of discussions around policy change and been given a platform by advocacy groups such as Obesity UK, Obesity Empowerment Network and the European Coalition of People Living with Obesity.

- Dr Adrian Brown, senior specialist dietitian, senior research fellow at UCL, and vice chair of the BDA Obesity Group, is currently collaborating with colleagues from UCL and the University of Leeds in a study supported by the BDA Obesity group to explore weight stigma in dietetic practice. If you are a dietitian, please take part in the survey (this can be done anonymously).

- Nutritank will soon be launching an online course for GPs and medical students on eliminating weight stigma, developed by Hala El-Shafie, Specialist RD in Eating Disorders and Bariatric Surgery, and founder of Nutrition Rocks.

Moving forwards

We asked dietitians for their expert views on next steps for addressing weight stigma…

Dr Adrian Brown said: “At the moment, a person can be discriminated against in the workplace due to their weight with no legal protection. There are still a lot of unanswered questions around whether weight and body size should be a protected characteristic like age, gender, disability or ethnicity and whether legislative action is the way to go.

“Now we are aware of the impact of weight stigma on people’s health, we have to do something about it. We have to start changing the environment and challenge stigma when we see it, whether that’s the language used by colleagues or in journals or the media. It might mean we have to have difficult conversations with people but it’s important we do this.

“As Desmond Tutu said, ‘If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor’.”

Hala El-Shafie believes: “If we really want to reduce weight stigma, we need to stop commenting on other people’s weight altogether, including people who are very slim as well as those at the heavier end of the weight spectrum. It’s not unusual for very slim women to experience stigmatising language and comments, for example, suggesting they have an eating disorder, need to ‘fatten up’ or ‘could do with a good meal inside them’. This can be very harmful. Praising someone when they’ve lost weight is also inappropriate – that person might have lost weight following a bereavement or because they have an illness where weight loss is not something to celebrate.

“Everyone working in healthcare settings, including receptionists, GPs, physios and nurses, should have training to eliminate weight stigma. This could start with an initial course for everyone in the workplace and then be included as part of the induction process for new staff. Avoiding weight stigma should be included as part of any anti-discrimination policy.

“I’d like to see all healthcare settings have a zero-tolerance policy towards weight stigma and promote ‘weight stigma free environments’, like they do ‘smoke free zones’.”

Anne Wright says: “There remains an outdated perception that dietitians need to be a certain size to do their job – neither too heavy nor too slim. It’s time for attitudes to change. A dietitian’s size or weight has absolutely no impact on their professional competence or ability to do their job. Even if a dietitian loses or gains weight, they’ll still have the same brain, the same knowledge and the same dietetic experience as before. Changes in their weight won’t affect the way they perform their job. The only difference will be that other people’s attitudes towards them will change.”

How you can help eliminate weight stigma in healthcare settings?

General recommendations

- Look at your own attitudes, beliefs and behaviours about weight – you may have stigmatising or discriminatory attitudes you’re not aware of. Take a questionnaire to gain self-awareness. You’ll also find questions to ask yourself in this presentation on Weight Bias in Clinical Care.Dr Adrian Brown says: “Although there has been research about weight stigma for decades, it’s only recently come to the forefront of discussions. As professionals we need to not be too critical on ourselves and accept if we recognise we’ve had stigmatising attitudes in the past, it’s about what we do in the future. Rather than dwelling on this, we need to draw a line under it, move forward and be more mindful about the language and attitudes we use in the future.”

- Improve your knowledge – obesity is a complex condition with genetic, biological and environmental factors playing a part. A greater understanding of the condition helps to reduce weight stigma.

- Gain an understanding of what weight stigma is like for patients – watch online videos where patients discuss their lived experience of weight stigma. “When individuals hear about the lived experience from people with obesity, there appears to be a reduction in stigmatising opinions,” Dr Brown explains

- Learn a new language – focus on respectful, supportive and empowering language, and avoid combative phrases such as ‘the obesity crisis’, ‘fighting obesity’ or ‘tackling obesity’.

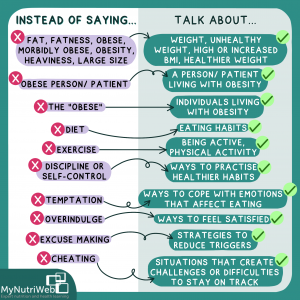

- Use a people-first approach – this means talking about a ‘person living with obesity’ rather than an ‘obese person’. For a list of stigmatising words to avoid, check out this Food Active! video at 1 hour 30 minutes.

Try these language swaps, too (click on the image to enlarge):

Anne Wright believes, “The move towards person-first language is a step in the right direction but we won’t get the narrative completely right until we lose all labels that mention weight or size. We just need to call our patient’s ‘people’, not ‘people living with obesity’. In my experience, most people know they’re overweight – they don’t need a label to tell them this.”

Make sure any leaflets or posters you use or produce avoid stigmatising language and images. This Food Active! resource will help you get it right. Plus, BDA members can access the BDA guidelines to ensure any content they create avoids stigmatising people living with obesity. To access these guidelines, BDA members need to login then search for ‘eliminating weight stigma’.

Use positive images of people wearing professional clothes, exercising or eating healthily rather than stereotypical ones of people wearing ill-fitting clothes, being sedentary or eating unhealthy foods. Several image banks provide non-stigmatising images for free:

- Challenge people if you hear them make negative comments about weight or size – both patients and colleagues of a larger size may experience stigmatising behaviour. Neither is acceptable.

- Be aware of how you speak about weight at all times, not just when talking directly to patients. It’s not unusual to hear colleagues talk about the ‘fat clinic’ or make derogatory comments, not just about patients, but also other colleagues.Anne Wright explains, “When it comes to weight, we need to apply the same non-stigmatising approach to our peers as well as our patients. It’s still common for health professionals to criticise colleagues who are heavier, often not directly to them but to other slimmer colleagues. Ultimately, we should afford the same kindness and courtesy to our colleagues as we do our patients.”

Recommendations when with clients

- Make sure you follow NICE guidelines on obesity – every patient should be treated equally, regardless of their weight, when it comes to treatment plans or referrals.

- Ask for permission to talk about weight – check with your patients if they even want to talk about weight and if so, what words they would prefer to be used when discussing this. The ‘right’ language to use is individual to each person.

- Ask patients about their experiences of weight stigma – it shows you have empathy and will help you assess how they cope and respond to weight stigma, providing you with more information to provide support.

- Step away from weight-focussed consultations – focus discussion on health and wellbeing rather than solely on weight loss as the main goal of change. “Rather than focussing solely on losing weight, it’s vital to look at the quality of a person’s diet and other behaviours that affect their health and eating habits such as movement, sleep and mindfulness. This will help to reduce the stigma that goes hand-in-hand with the ‘just eat less and exercise more’ mantra,” says Hala El-Shafie

- Consider whether you really need to weigh someone – ask yourself whether you’d weigh that person if they were slimmer. If it’s necessary, ask them when they’d prefer to be weighed. “It’s important to make sure health-focussed conversations don’t end up with weight creeping back into the dialogue. We might set out to focus on health but it’s easy to slip back into more familiar weight loss territory, for example, weighing a patient or setting weight loss goals.” Anne Wright

- Consider your own non-verbal cues – could your body language, tone of voice, facial expressions, gestures or eye contact be considered stigmatising?

- Get into the habit of reflective practice at the end of each patient contact to help you recognise any stigmatising attitudes – look at what went well, what language was used, what other strategies could have been used and what could be done differently next time.

- Consider practical elements to reduce stigma – ensure healthcare settings are suitable for people of every size and weight, with appropriately-sized medical equipment, wheelchairs, chairs and robes.

Additional Resources

Follow author Juliette Kellow on Instagram: @juliettekellownutritonist

Thank you so much for this excellent piece! So many links and resources on top of the important message it mediates.

Thank you for your comment – great to hear. It’s such an important topic & there’s so much to learn.

This is all still pretty unhelpful as it frames being fat as a problem and tries to use alternative language to disguise the exact same stigmatising approach. I’m still going to avoid doctors who talk about eating habits rather than diet when what I need is healthcare. I’m not an idiot. Also people with obesity is a gross phrase, I’ve only seen thin people advocate for it.

I’m at a loss for where to even begin with this. This is a blog post about how bad weight stigma and stigmatizing behaviors are that is chock full of stigmatizing misinformation and awful recommendations. I would highly recommend the authors spend some time really digging into the science instead of blithely repeating weight loss zeitgeist. Here are some simple steps to take that won’t increase the suffering of the people who are most often targeted by weight bias, stigma, and discrimination:

1) DO NOT use BMI as a measure of health. There is no science that supports this ratio as a predictor of health outcomes.

2) DO NOT encourage weight loss as a treatment for anything. Again, the science says that people who lose weight for the sake of losing weight have significantly worse health outcomes than those who maintain a higher weight.

3) DO NOT encourage weight blindness. For a lot of the same reasons that colorblindness is a harmful approach to racism, weight blindness further puts higher weight people at risk. We need to emphasize that there is nothing inherently wrong with weighing more, and stop falsely attaching poor health outcomes to weight through specious correlations.

4) DO get in the habit of uninvesting in anyone’s weight or size. For the vast majority of heavier people, the reality is that their best chances at having long and happy lives lie in unlearning the idea that thinness is required for “health.” Bariatric surgery does not work long term. Dieting is harmful. We do not, at current, have any actual medicine that makes heavy people into thin people who live happily ever after in their thin bodies, and we don’t have best practices or habits that can deliver that to the vast majority of people. There’s still too much about how our bodies work that we don’t understand, and pretending that’s otherwise is doing constant and unnecessary harm.

Thinness isn’t required for value. Seeking thinness isn’t required for value. Wanting thinness isn’t required for value. So much of this post reads like, “if we trick all the heavier people into thinking we don’t judge them, we can turn them into the happy, healthy, and, most importantly, THIN people they were always meant to be!” And that’s just flat wrong.