When it comes to diabetes management, carbohydrate intake is a controversial topic – with considerable inconsistencies in international recommendations. Research suggests there is no ideal percentage of energy of macronutrients for patients with diabetes; rather, we should take an overall perspective of the quality of their diet. Despite this research, there is still confusion among patients and professionals alike.

Understanding patients & dietitians

Registered Dietitian and diabetes specialist Dr Paul McArdle investigated the area of uncertainty and concern among patients and dietitians for his PhD research. Although most dietitians supported low carbohydrate diets for glycaemic control and weight loss, there were concerns about both the overall quality and practicality of such diets (Huntriss, Boocock & McArdle 2019).

The research also revealed many challenges faced by patients. These included a limited understanding of carbohydrates and recall of the advice they received from professionals. Alongside these were other important influences on dietary changes in their life that had been overlooked, including social factors and even their food likes and dislikes.

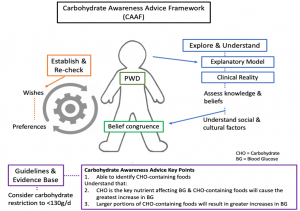

As a result, the team developed an important tool to support health professionals in providing better education and care to patients on carbohydrates and diet quality – the Carbohydrate Awareness Advice Framework (CAAF).

The first step in the CAAF model is to explore and understand the patient’s knowledge and start to educate them on carbohydrates. However, helping patients with diabetes (PWD) to understand that not all carbohydrates are created equal can be difficult, as they often view carbohydrate through a ‘sugar lens’.

Using a dietary pattern approach can help patients consider their overall diet quality as they manage their blood glucose levels and make smart choices in the types of foods they consume. This approach is often focused on food, rather than individual nutrients, and offers flexibility in the quantities of macronutrients.

There are several dietary patterns that can be suitable for patients with type 2 diabetes, including;

- Mediterranean

- Healthy Nordic

- Low Fat

- DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension)

- Low Carbohydrate

- Low Glycaemic Index / Load diets

But it is important that advice given is individual to the patient and considers their lifestyle and personal preferences.

Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load

Another topic that causes confusion is Glycaemic Index (GI). GI is complex not least because it relies on a good baseline understanding of carbohydrate, plus there are considerable inconsistencies in the data and exceptions to the ‘rule’. Adding this next level of complexity is hard for many patients and professionals.

The first hurdle is that there are many different GI values for the same food – often spanning the different categories of high/medium or medium/low. The most comprehensive database for GI values is held by the University of Sydney (www.glycemicindex.com), backed by extensive research led by Professor Jennie Brand-Miller. However, much of the research to determine GI values of foods has been done in relatively small samples in people without diabetes. Most research on GI in the diabetic population has been carried out in Type 2 Diabetes, so there is not much evidence for its use in Type 1 Diabetes.

The size of the effect GI has on blood glucose is also up for debate. Since its growth as an interest area 15-20 years ago, research suggests the size of the effect on blood glucose is smaller than originally thought.

That being said, most people understand the concept of ‘faster acting’ and ‘slower acting’ carbohydrates when it comes to the effect on their blood glucose, particularly in diabetes. So using this as a tool to help patients to understand the effect certain foods may have on their blood glucose levels can be helpful.

Another problem is that GI can be taken out of context. For example, the GI of a chocolate bar can be less than the GI of bread. But does that mean the chocolate bar is ‘healthier’? Another example would be the GI of jelly sweets (very high GI) compared to pasta (medium/low GI). You’d typically have a much larger portion of pasta than jelly sweets (hopefully!), so we need to be able to explain that whilst the jelly sweets have a higher GI than the pasta, this generally wouldn’t translate into a higher impact on blood glucose if a very small portion is eaten.

This is the concept of Glycaemic Load (GL) – combining the GI with the amount of carbohydrate in a food to get a more accurate predictor of the effect on blood glucose: (Carb (g) x Glycaemic Index)/100.

The promotion of foods with a low GI or GL can fit into many different dietary approaches for the management of Type 2 Diabetes. Typically, low GI or GL foods are minimally processed, and although they are not all necessarily ‘low’ in carbohydrate, that doesn’t mean that they are ‘high’ in carbohydrate.

To learn more about the evidence on low carbohydrate diets for patients with Type 2 Diabetes, catch up on our webinar Carb Confusion: Carbohydrates & Type 2 Diabetes, developed in partnership with Diabetes UK. In this webinar, Dr Paul McArdle discusses the evidence, his PhD research and offers practical guidance for health professionals.