By Samantha Blamires, Specialist Paediatric Allergy Dietitian

Do you have the knowledge and skills to recognise and manage infants and young children presenting with symptoms of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES)? A recent study has suggested a lack of awareness amongst UK healthcare professionals in recognising FPIES, leading to delays in diagnosis and access to appropriate management(1). This blog aims to provide an overview of the current evidence base for the diagnosis and dietary management of FPIES. At the end of the article you are signposted to additional resources to support your continued professional development in this area, and resources to use with your patients.

What is FPIES?

Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, also known as FPIES, is a non-igE mediated (delayed-type) food allergy. It typically presents in infancy and is characterised by repetitive, protracted vomiting which starts 1-4 hours after ingestion of a trigger food. It is often accompanied by lethargy, pallor and floppiness, and may be followed by watery/bloody diarrhoea(2).

FPIES should be considered a potential medical emergency as, left untreated, 15% of acute FPIES reactions can progress to acidosis, hypotension and shock(3). Despite the potential seriousness of reactions, awareness of FPIES is low(3) and a recent British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU) study highlighted the need for improved healthcare professional education to improve recognition, earlier diagnosis and treatment(1). Under-recognition by healthcare professionals is associated with significant delays in diagnosis, with one study reporting delays of up to 15 months before an accurate diagnosis is made, with many infants experiencing 3 or more FPIES reactions during this time(1).

How common is FPIES?

The prevalence of FPIES is largely unknown(4), however current estimates range from 0.015-0.7% (1.5 to 7 FPIES cases per 10,000 live births)(2). The lack of epidemiological data relates to the fact that FPIES was not recognised or formally defined until the mid-1970s, and the diagnostic code for FPIES was not implemented until 2015.(4) There are also no known diagnostic biomarkers available and diagnosis relies on a good allergy focussed clinical history, which leaves the condition vulnerable to misdiagnosis(4).

A recent prospective survey of FPIES in the UK and Ireland reported an incidence of 0.006% (0.6 cases per 10,000 live births per year) for England alone, but the authors concluded that this was likely to be an underestimate resulting from under-recognition by healthcare professionals(1). It is also conceivable that milder cases presented to primary care, and were therefore not picked up within the surveillance data. An editorial(4) written by two authors of the FPIES International Consensus Guidelines(3)noted a steady increase in peer-reviewed reports of FPIES and suggested that this could point to a possible increase in prevalence over the past 1 to 2 decades(4). So, if we consider the likely under-recognition, misdiagnosis, and increased case reports, perhaps FPIES isn’t so rare after all?

Recognition and Diagnosis

Recognition and diagnosis is reliant upon a good clinical history followed by resolution of symptoms on elimination of the suspected trigger food(s)(3). Given that the symptoms of FPIES can often mimic other serious conditions e.g. sepsis, it is important that the diagnosing clinician rules out the possibility of any differential diagnoses (these can be found in Table III of the International Consensus Guidelines(3)).

What should a good clinical history include?(3)

- Details of all possible reactions

- Specific symptoms

- Timing of symptoms in relation to food intake

- Any suspected food triggers?

- Have there been reproducible reactions on repeated exposure to the suspected food(s)?

The history alone is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis, however if there is uncertainty, or the history is unclear then an oral food challenge is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis(3).

Are there any diagnostic criteria that can be referred to?

FPIES is a heterogeneous condition which varies both in its presentation and severity(3). The frequency and dose of the trigger food, along with observable characteristics (phenotype) and age of the patient determine whether FPIES is acute , chronic, or atypical in its presentation(3). Tables 1 and 2 outline the diagnostic criteria for acute and chronic FPIES respectively. When used alongside a detailed allergy focused clinical history the criteria can help to confirm the diagnosis and its classification.

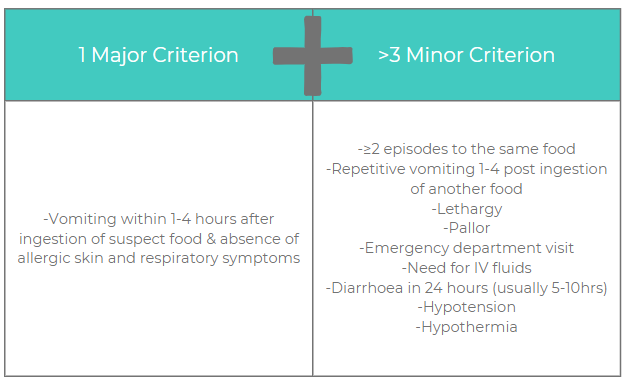

Diagnostic criteria for acute FPIES

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for acute FPIES. Adapted from the International Consensus Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of FPIES(3). A diagnosis of acute FPIES requires the patient to meet the major criterion plus ≥3 minor criteria. If only a single episode has occurred, a diagnostic oral food challenge should be strongly considered to confirm the diagnosis, especially because viral gastroenteritis is so common in this age group.

Diagnostic criteria for chronic FPIES

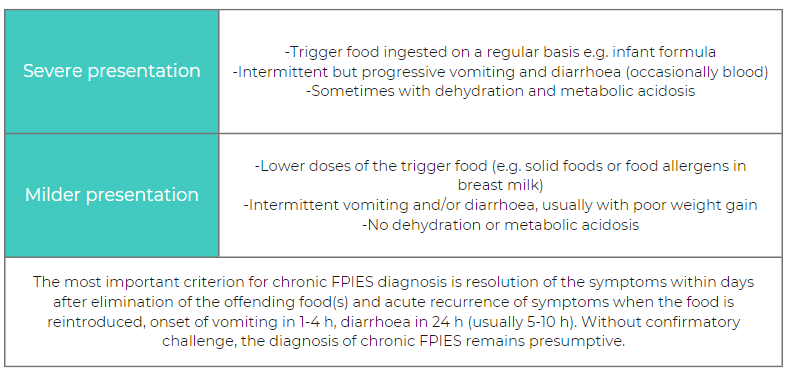

Chronic FPIES is less well-characterised than acute FPIES and only reported in infants <4 months of age fed with cow’s milk or soy based infant formula(3).

Table 2. Diagnostic criteria for chronic FPIES. Adapted from the International Consensus Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of FPIES(3).

Can skin prick tests or specific IgE blood tests inform the diagnosis(3)?

As previously eluded, there are no diagnostic biomarkers for FPIES. The pathophysiology of FPIES is poorly understood, but as it a non-IgE mediated process, tests for allergic sensitisation (skin prick test and specific IgE blood tests (sIgE)) should not be routinely performed to inform the diagnsosis.

Most infants with FPIES have negative skin prick test responses and undetectable sIgE to their trigger food at initial presentation(3). However, some children present with positive sIgE to their trigger food (known as atypical FPIES) and therefore guidelines recommend considering periodic testing for patients who have other comorbid atopic conditions e.g. IgE mediated food allergy to other foods, or atopic dermatitis exacerbated by a food allergen(3).

In a US study 41% of children with atypical milk FPIES converted to an IgE-mediated phenotype after a period of milk exclusion(5). Therefore, in patients with FPIES to cow’s milk it is recommended that sIgE is measured before performing a resolution food challenge(3). This will determine whether an FPIES food challenge protocol can be used, or whether a more cautious, graded approach is needed as would be used for children with IgE mediated food allergy.

What are the most common food triggers?

Food triggers vary based on geographical location, as do the number of food triggers reported per patient. In a recent systematic review which looked at the most frequently reported food triggers, cow’s milk, fish, hen’s egg, grains (rice and oat), and soy were reported to be the most common triggers worldwide. This is reflected in a prospective survey of FPIES in the UK which found the most common food triggers in the UK to be cow’s milk, egg, fruits and vegetables, and fish(1).

The majority of children will have a single food trigger (65-80%)(3). It is uncommon to react to 2 or more foods, however one US centre reported that 5-10% of their cohort reacted to > 3 foods, with some reacting to as many as 6 or more. A study by Mehr and colleagues identified early onset of FPIES (before 5 months of age) and reactions to fruits and vegetables (or both) as risk factors for having FPIES with multiple food triggers(8). This might help us to identify those infants who would benefit from additional support with solid-food introduction(4).

Dietary Management

The management of FPIES relies on the avoidance of food triggers, treatment of accidental exposures, and periodic supervised oral food challenges to monitor for resolution(2). It is recommended that all children with FPIES receive support from a registered dietitian to assess the nutritional adequacy of their diet and reduce the risk of nutritional deficiencies arising. Children with food allergy have been noted to have deficiencies in energy, protein, vitamin A, vitamin D, calcium, iron, and zinc. Nutritional deficiencies may arise as a result of dietary restrictions and delayed introduction of new foods so it is particularly important that families can access support from a specialist paediatric allergy dietitian to guide them through the weaning process(3).

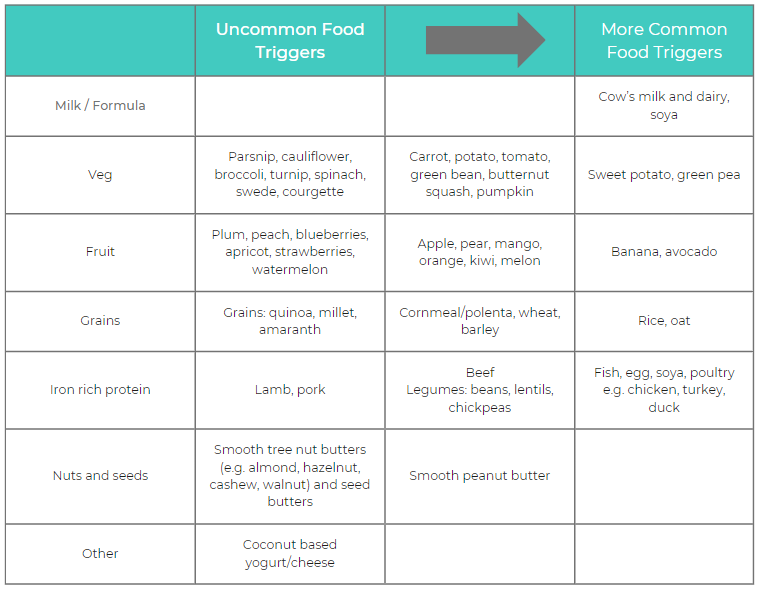

The introduction of complementary foods should not be delayed as it is important for infants and young children to experience a wide variety of foods, tastes and textures. In many respects the advice around introducing complementary foods is similar to that given for infants without FPIES i.e. to introduce a wide-range of solid foods, including iron-containing foods, in an age appropriate form, from around 6 months of age, alongside continued breastfeeding(9). As a general rule, for infants with a known FPIES reaction, parents are advised to introduce one new food at a time, starting with one teaspoon of the food and increasing the amount gradually over a maximum of 3 days(10). It is advisable to give the new food by midday so that any reaction occurs during daytime hours. Once the child has tolerated the food, this food and any previously tolerated foods, should remain in the diet whilst another new food is introduced(10). If parents are particularly worried about introducing new foods, or their child has multiple food triggers, then a more cautious approach may be advised. This approach starts with the introduction of uncommon food triggers and gradually progresses to more common food triggers (Table 3). Parents may be reassured to know that tolerance to one food from a food group (e.g. green pea) is a favourable indicator of tolerance to other foods from the same food group (e.g. legumes)(3).

Table 3. Frequently reported food triggers: A guide to complementary feeding in infants with FPIES. Table adapted from BDA Food Allergy Specialist Group: Introducing solids to your baby with FPIES(10)(3)(1).

When assessing the nutritional adequacy of the diet it is helpful to consider the main nutrients that are typically provided by the food trigger. This will enable you to support families to find alternative sources of key nutrients that may otherwise be limited by avoidance of the food.

Other common questions that you may be asked when supporting families with food exclusion include: should I exclude the trigger food from my own diet (in the case of a breastfeeding mother)? And, do we need to exclude foods with precautionary labelling (e.g. may contain milk)?

In terms of breastfeeding, the majority of infants will not react to food allergens present in breast milk and therefore exclusion of the food trigger from the maternal diet is rarely indicated(3). This is usually only considered in cases of infants who are exclusively breastfed and symptomatic after breast feeds and/or present with faltering growth. For precautionary labelling, current guidelines do not recommend avoidance of foods carrying ‘may contain’ labels(3).

Resolution of FPIES

On initial presentation, symptoms of acute FPIES usually resolve within 24 hours after ingestion of the food trigger. The child is typically well between episodes and has normal growth. In the case of chronic FPIES, symptoms usually resolve within days after elimination of the food trigger, however subsequent exposure to the offending food(s) results in an acute FPIES reaction with onset of vomiting within 1-4 hours post ingestion(3).

However, what parents really want to know is “will my child ever grow out of their FPIES”? For the majority of children the answer will be yes, with most outgrowing FPIES by 3-4 years of age. However the actual age of tolerance acquisition varies based on the food trigger and country of origin. Tolerance to cow’s milk and soy is typically acquired earlier than grain- or other food-triggered FPIES, and in some cases, FPIES persists into adolescence and adulthood.

There are no known strategies to accelerate development of tolerance in FPIES(2), and the only way to assess tolerance acquisition is with a hospital-based oral food challenge(3).

Summary

FPIES is a complex presentation of non-IgE mediated food allergy(1)which requires the knowledge and expertise of a specialist registered dietitian to ensure nutritional adequacy of the diet whilst successfully eliminating the suspected food trigger(s). Dietary management should include advice on complementary feeding (where this has not yet occurred or has been delayed), allergen avoidance, safe foods, and an assessment of the nutritional adequacy of the diet to support appropriate growth and development.

Useful resources

FPIES UK – a UK charity dedicated to FPIES which produces resources and education for parents and HCPs

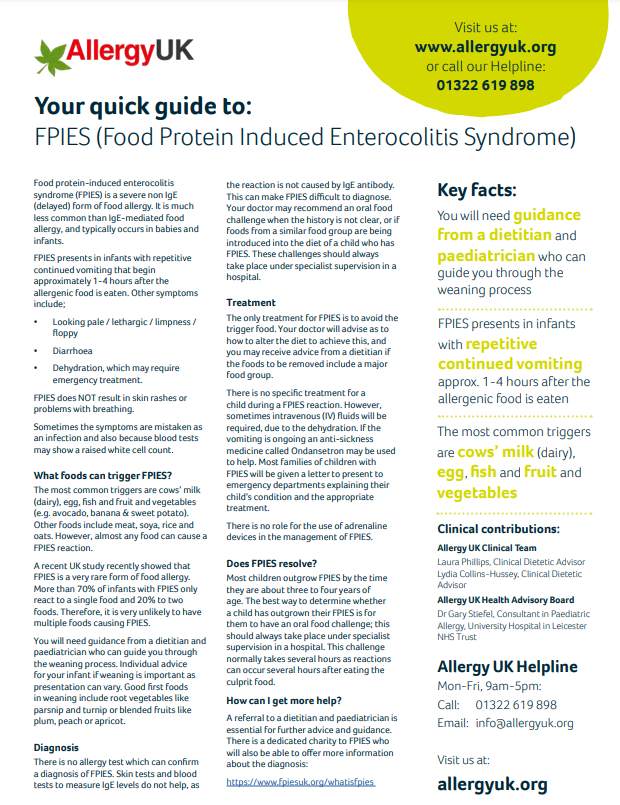

Allergy UK – FPIES factsheet

BDA FASG – Members of the BDA Food Allergy Specialist Group can access their comprehensive diet sheet ‘Introducing solids to your baby with FPIES’ via the members area of the website

![]()

I was born in the 1970’s, and with a diagnosis of intolerance to cow’s milk and soya, I spent much of my first year in and out of hospital. I did outgrow it around age 3-4, but it came back in my early 40’s.

I have 4 children and the youngest has the same problem, with the inclusion of hen’s eggs. However, he is 14 now and he has not outgrown it at all.

As we are both intolerant to anything that “may contain” these products, as well, we both follow a vegan diet as an alternative to milk, soya and eggs.

Thank you for your blog, it has been most informative.