Author: Francesca Allsop, HCPC Registered Dietitian working at HMP Berwyn (the UK’s largest prison) since December 2020.

Author: Francesca Allsop, HCPC Registered Dietitian working at HMP Berwyn (the UK’s largest prison) since December 2020.

Do you know any dietitians that work a prison? Probably not. There are not enough of us. Supporting this year’s Dietitian’s Week, this blog promotes role of the prison dietitian and shows just how essential dietitians are to this sector.

Incarceration provides prisoners an opportunity to access education, learn a trade, access healthcare, process their behaviours and ultimately aim to reform. Being a dietitian in a prison allows access to vulnerable communities on their transition back to ‘normal life’. A real difference can be made to this population group, it is a privilege.

Prisons in the UK: some background information

There are 121 prisons in England and Wales and the total prison population stands at around 79,000. I work at HMP Berwyn in North Wales, which is the largest prison in the UK with a capacity for 2,106 men. At the time of writing, the age of the prisoners ranges from 18 to 85, with the average age being 36.

The UK has the highest imprisonment rate in western Europe and the population of prisons here has risen by 69 per cent in the last 30 years.

What is a prison dietitian?

The role of a prison dietitian is to provide first-line dietetic advice and intervention to patients within the prison walls, equalising healthcare accessibility in a way similar to the rest of society. A prison dietetic role involves introducing complex nutritional science into everyday living, using lay terminology that is appropriate for an incarcerated lifestyle.

Dietetic provisions across UK prisons are sparse, with only 9 per cent offering any form of in house service and most outsourcing dietitians from local NHS services. Being in prison can make access to external health care challenging and security staff must weigh-up the risks versus benefit of facilitating off site appointments. Evidence shows that 42 per cent of outpatient appointments for prisoners are not attended, compared to 23 per cent of the general population.

Healthcare needs of prisoners

Prisoners have the same healthcare needs as the general population – or do they?

According to a recent literature review, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of natural deaths in prisoners. Evidence from 2020 suggests that comorbidities (hypertension, Type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease and obesity) are similar to that of community levels – but they are present in a population 10 years younger. Type 2 Diabetes prevalence amongst the prison population is increasing and there is an abundance of cardiometabolic risk factors not being diagnosed.

Prisoners are also more likely to have experienced abuse, been in the care system, experienced unemployment and homelessness. This equates to significant mental health needs and more complex physical needs, evidenced by record high levels of self-harm rates and self-inflicted death rates.

Nutritional management and responsibilities

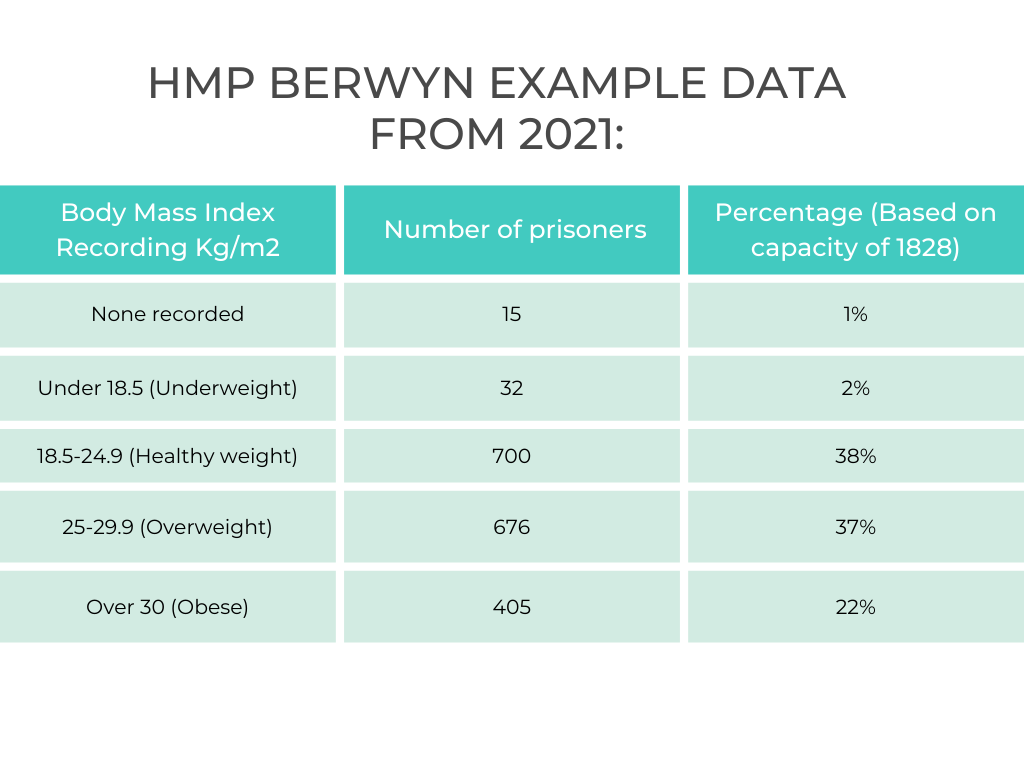

Dietetic input is hugely varied in a prison environment, and we can see from the data below that there is an un-met health need across all prisons when it comes to service provision for obesity management – arguably a public health crisis.

BMI for HMP Berwyn prisoners

Note: some of these statistics are skewed by high muscle mass, prevalent due to prison gym culture.

So at HMP Berwyn, what does a dietitian do?

My role includes a one-to-one clinic, weight reduction support groups, and regular meetings with kitchens and health promotion strategy coordinators.

Patient groups seen are highly variable to include patients with obesity, diabetes, gastroenterology related conditions and malnourished patients.

In addition to this work, I also works to ensure safe management of food refusal prisoners at risk of refeeding syndrome (defined as the ‘metabolic changes that occur on the reintroduction of nutrition to in those who are malnourished or in the starved state’).

Dietetic challenges in a prison

A prison environment is a niche setting, with multiple barriers to delivery of effective dietetic care.

50 per cent of prisoners are functionally illiterate, with 25 cent having reading skills below those of an average seven-year-old. Educational barriers make translation of complex nutritional science difficult.

Healthcare workers can be subject to coercive behaviour from prisoners; some prisoners may aim to access privileges through healthcare staff to include special diets, medication or extra gym time. Both social and medication prescribing is a risk in a prison environment, as everything is highly tradable.

Prison food budget is £2.02 per prisoner, per day. Public Health England suggests a balanced diet costs £5.99, arguably indicating prisoners’ nutritional health is overlooked by funding bodies.

Many prisoners are dissatisfied with the food offered in prison. Nutritional intake is greatly impacted by additional self-funded snacks – these are often high in saturated fats and sugars. This makes it difficult for prisoners to implement the advice given by dietetics.

Advice for dietitians interested in pursuing prison work

Healthcare in prisons is provided by both the NHS and independent operators, so look out for job opportunities across both sectors.

You must be resilient and learn to deal with confrontation to work well in this setting. Learning to communicate and deescalate is essential. It is also important to show compassion to all prisoners, as it is not always possible to know or understand their complex backgrounds.

Dietitians can have a very positive outcomes in this environment. Prisoners are often respectful and grateful for advice, using their sentence as an opportunity to make changes to better their health.

The place of work is different and how you approach things may be different but it’s still about supporting people with their diet and healthcare. Here’s just a few examples of some of the work I have done:

A patient had been referred with the dietetics reason being stated as “IBS and new diabetes”. During clinic I knew something wasn’t right. This patient reported Type 7 stools 20+ times per day, so I requested further investigations. When the results came back they showed that this patient actually had pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and type 3c diabetes. After obtaining the correct diagnosis I requested the consultant prescribe pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), counselled the patient on how to use this and now all his bowel symptoms have completely resolved. The next challenge is diabetic management!

Another example is where I have been supporting a patient with weight loss over the last 19 months. He has intentionally lost 85kg (13 stone!!) in that time and his BMI has reduced from 65kg/m2 to 38kg/m2. He told one of my colleagues this week “Fran and my mum are the only people I trust and am honest with”.

If you have any thoughts or questions about the role and how it works, leave a comment in the box below’

Hi, would like to know how much calories does a prisoner need per day? Does 2 pounds budget enough for a day- towards a healthy diet?also who prepares the food for prisoners?

Could you share the working papers on prisoner diet?

Response from Fran: “Calories vary per person, the average typical man require 2500kcal/day but prisoners lead a more sedentary lifestyle than those free living individuals this requirement is based off. A 2 pound budget is difficult to meet nutritional requirements, but it can be done when buying in bulk. About 100 prisoners have paid employment and work in the prison kitchens alongside external catering staff to oversee/manage. There isn’t much evidence base for prisoners dietary intake at present. I’d encourage you to have a look at the work Food Behind Bars does. “

Is there a possibility that healthier snacks can be introduced into prisons ? Nut and seed products for example?

Can prisoners buy fruit?

Is dark chocolate available?

Great Blog !

Response from Fran: “Thank you. In short answer, yes they are all available for prisoners to buy at the moment, but can often be expensive on a prisoners canteen shop (e.g. they only earn £11 a week but an avocado costs them £1.30 and easy peelers £2.50). In long answer, the budget is really tight for the kitchens and fruit, vegetables, nuts, seeds are not always cheap or easy to store. Lots of barriers and some resistance to change. We do have a ‘’healthy option’’ on the menu, so I encourage men to pick that. You can achieve a healthy diet as a prisoner if you have the knowledge base to do so.”

With regard to illiteracy, could a picture based leaflet be given to inmates?

I designed one some time ago for mental health patients unable to to read (English). Using ticks and crosses to indicate more of and less of. I loved the old poster with the muscular gorilla (“you think fruit and veg are for only for whimps ” – I think) !!

Response from Fran: “Picture based ‘’easy to read’’ leaflets have been created for the prisoners for most dietetic needs. Especially for those with important dietary restrictions, such as coeliac disease. I am always looking for more patient resources that have been developed that work in practice, please get in touch if you’re able to share any.”

great article!

So glad you enjoyed it!

Hello,

Thank you for this informative blog.

I recently graduated with BSc in Hons Nutritional sciences and wondered what kind of steps would I need to take to get into providing health advice in prisons? It is difficult to find any work placements/or job roles even as a dietetics assistant in prisons within my region (Northwest, Manchester).

I would be interested to gain some experience even if it is remote.

Please get in touch if this is something you feel like you would like to discuss further?

Thanks once again for shedding light on such an important topic!

Response from Fran:

I am pleased you enjoyed it. It depends what advice you wish to give. You would be qualified to apply for a health promotion, public health role. You would have to train to be a dietitian to provide input for clinical conditions. Prison health is poorly funded, not many opportunities come up sadly. My advice would be to reach out to local prisons and ask them if they have a health promotion strategy and if they’re looking to fill any jobs to supporting that strategy. There will be a band 4 therapy assistant job advertised at HMP Berwyn soon, which will include dietetic support work if interested. Thanks, Fran

Thanks again Fran for highlighting the varied role of the Dietitian in a prison environment. With regards to the comments on Jobs. – i just wanted to flag up there is a current advert out for Dietitian on HMP IOW, and we are due to advertise for Dietetic Assistants in Thames Valley Prisons Cluster. Please do watch out for Practice Plus Group Jobs as well as NHS if you are interested in this area

I would like to know the roles and responsibilities of a dietetic assistant practitioner in prison setting.

Response from Fran: “We don’t have a dietetic assistant in the prison at the moment, so cannot give you a specific answer. However, there is scope for this role in a prison environment. In Wales they’d be able to run the “Foodwise” education program, triage dietetic referrals, provide routine follow ups under dietetic supervision and be the liaison with kitchen regarding special dietary provisions”