By Abigail Perry, Specialist Dietitian and Anna Stephanou, Specialist Dietitian

Dietary factors that affect the risk of pre-eclampsia

This article provides a snapshot of the work conducted by RD Abigail Perry, RD Anna Stephanou and Professor Margaret Rayman into dietary factors that affect the risk of pre-eclampsia. This work has been published in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health with open access and may be found online.

What is pre-eclampsia?

Pre-eclampsia occurs in pregnancy and is defined by hypertension after 20 weeks gestation alongside maternal organ dysfunction, with or without the presence of protein in the urine. Pre-eclampsia may be classed as early onset, occurring before 34 weeks gestation, or late onset, which occurs after 34 weeks. This condition is progressive and its severity varies between those affected.

What causes pre-eclampsia?

During pregnancy, if vital placental arteries (the spiral arteries) fail to develop into larger, low resistance vessels, this results in poor perfusion of the placenta. This poor perfusion leads to cellular stress which results in the release of antiangiogenic factors (these factors inhibit the growth of new blood vessels). The release of these factors induce systemic endothelial dysfunction, which then presents as the symptoms observed in pre-eclampsia.

Prevalence

Pre-eclampsia affects 3-5% of women worldwide. There appears to be variation in the incidence of pre-eclampsia regionally; with incidence being higher in upper middle income countries compared to lower income countries.

Who is at risk?

Multiple factors can place an individual at heightened risk of pre-eclampsia. For example, those who have had previous pre-eclampsia are more likely to suffer from the condition in a future pregnancy. Furthermore, those with certain health conditions such as chronic hypertension, pregestational diabetes, renal disease, obesity and autoimmune disease are also at heightened risk. Maternal age >35 years and multifetal gestation also heighten the risk of pre-eclampsia. It is also interesting to note that the state of not having previously born offspring (also known as the nulliparous state) appears to be the most prevalent risk factor of pre-eclampsia.

Clinical presentation and implications

Pre-eclampsia may result in prematurity of the foetus and intrauterine growth restriction. Poor development in early life may lead to heightened risk of health conditions in the child’s future. Pre-eclampsia may also affect the mother, often presenting as maternal organ dysfunction. This can affect multiple organs such as the uterus, kidneys, liver, blood and brain. In some instances, pre-eclampsia may result in death of the mother or the foetus. Pre-eclampsia is estimated to cause 42,000 maternal deaths annually worldwide.

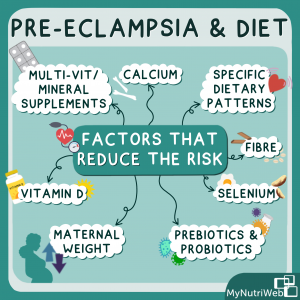

Nutritional and dietary factors

From the latter part of the last century, a range of dietary components were suggested as having the potential to reduce pre-eclampsia risk. These dietary components include vitamin C and E, fish oils or omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA), magnesium, zinc supplementation and salt. However, recent evidence shows that these factors have no significant effect on reducing the risk. Factors that have been found to reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia include maternal weight, fibre, vitamin D, calcium, selenium, prebiotics, and probiotics, multivitamin/mineral supplementation and specific dietary patterns.

Maternal body weight and BMI

Research shows that heightened body mass index increases risk of pre-eclampsia, with pregnant women with a BMI >30 being at a 1.8-fold greater risk of developing pre-eclampsia compared to pregnant women with a BMI of 20-24.9.

Gestational weight gain above that recommended is also known to increase pre-eclampsia risk. This has been observed in women who became pregnant for the first time with a BMI >19. In this cohort, a 1kg increase in gestational weight gain was associated with a 1.3 times greater risk of pre-eclampsia.

As body mass index is proportionally correlated with pre-eclampsia risk, excessive weight gain during pregnancy and between pregnancies should be avoided. Table 1 shows the recommended total weight gain during pregnancy, as advised by the Institute of Medicine, based on pre-pregnancy BMI.

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index (kg/m2) | Recommended total weight gain (kg) |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 12.5-18 |

| Healthy Weight (18.5-24.9) | 11.5-16 |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 7-11.5 |

| Obese (>/= 30) | 5-9 |

A woman aiming to reduce her BMI prior to pregnancy should do so safely with the help of a suitable healthcare professional such as a dietitian.

Fibre

Dietary fibre may be able to attenuate the dyslipidaemia seen in pre-eclampsia. Pre-eclamptic women have higher serum triglycerides and LDL cholesterol in comparison to normotensive women (those with normal blood pressure, within the healthy range). Increased fibre intake may reduce blood pressure and inflammation. Increased dietary fibre intake may also aid in weight maintenance.

A case-control study found fibre intake to be inversely associated with risk of pre-eclampsia. This study showed that women who had >24.3g fibre/day had a 51% reduced risk of developing pre-eclampsia compared to those who had <13.1g/day.

A high-fibre diet is recommended for pregnant women and those at risk of pre-eclampsia, aiming for a fibre intake of 25-30 g/day to reduce the risk. Available evidence also suggests amounts above 30g/day should not be recommended. Dietary fibre can be found in starchy carbohydrates such as oats, breakfast cereals, wholemeal bread and pasta, potatoes (skin on), sweet potatoes. Other sources include beans, pulses, fruits, vegetables and seeds such as linseeds and chia seeds.

Dietary Patterns

Dietary patterns before and during pregnancy play an important role in the development of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Although limited, there is observational evidence to suggest that diets higher in fruits and vegetables, nuts, whole grains, legumes, fish and vegetable oils are protective against hypertensive disorders. This observational evidence is outlined in detail within our aforementioned published article.

Pregnant women should aim to consume ≥400 g of fruit and vegetables per day (equivalent to 5-a-day) and ≥250 mg/d docosahexaenoic/eicosapentaenoic (DHA/EPA) acid by consuming ~230 g of mixed seafood per week) – equivalent to about 2 portions. High fat, salt, sugar foods, red and processed meats should be limited in the diet. Raw fish and fish with a high mercury content (shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, marlin, orange rough, bigeye tuna) should be avoided during pregnancy.

For general advice around eating well and safely during pregnancy, see the NHS. MyNutriWeb also have a webinar available with advice for those following a plant-based diet during pregnancy.

Prebiotics and Probiotics

Differences have been observed between the gut microbiota of pre-eclamptic and normotensive women, with those with pre-eclampsia having a relatively greater proportion of pathogenic bacteria and fewer probiotic bacteria. Probiotics may aid in reducing inflammation and have also been shown to have antihypertensive effects when consumed alongside dairy products (which act as prebiotics).

Indeed, Brantsæter et al. found that in a cohort of 33,399 nulliparous women, intake of milk-based probiotics reduced risk of severe pre-eclampsia. However, later investigation revealed that probiotic milk intake is only associated with reduced risk of pre-eclampsia if consumed in late pregnancy.

Milk-based probiotics are recommended to be consumed where possible as part of a normal diet. Further research is required to determine the quantity, timing, and efficacy of probiotics to reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D may play a protective role against pre-eclampsia through modulating pro-inflammatory responses, promoting the formation of new blood vessels and decreasing blood pressure. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with dysfunction of the endothelial tissue lining the interior surface of our blood vessels whereas replacing vitamin D can lower oxidative stress.

There is some evidence to suggest that vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy reduces risk of pre-eclampsia. A meta-analysis and systematic review conducted by Khaing et al. found that vitamin D supplementation reduces risk of pre-eclampsia by 57%; however, this was not found to be statistically significant. Some research investigating the relationship between vitamin D supplementation and pre-eclampsia risk are inconclusive. Further well-designed studies to better define the association are warranted.

In line with recommendations made by Public Health England and the Institute of Medicine, pregnant women should take a daily vitamin D supplement of 10-25 μg (400-1000 IU) to reduce risk of inadequate vitamin D status. Ideally, this should be commenced prior to conception.

Calcium

Low calcium intake results in low intracellular calcium concentration. This in turn causes vasoconstriction, increased vascular resistance and increased blood pressure. Increased calcium intake may help reduce risk of pre-eclampsia by reducing arterial vasoconstriction in the uterus and placenta. Some research also suggests calcium may have an anti-inflammatory effect.

Calcium supplementation in pregnancy reduces risk of pre-eclampsia. The protective effect of calcium supplementation is well established with doses ≥1 g per day with less research available on doses of <1 g per day.

Calcium supplementation of 1 g per day from 20 weeks gestation to delivery in the form of calcium carbonate or calcium citrate is recommended. Women who are at a heightened risk of pre-eclampsia and/or have a low dietary calcium intake should take a calcium supplement of 1-2g/day during pregnancy. Dairy and dairy products such as milk, cheese, yoghurt are sources of calcium. Calcium is also found in plant-based alternatives to dairy such as fortified plant-based milk alternatives and yoghurts. Other sources of calcium include green leafy vegetables and broccoli, sesame seeds, calcium set tofu, dried figs, almonds, fortified cereals and bread and fortified orange juice.

Selenium

Selenium is essential to form selenocysteine, a component of functional selenoproteins including the glutathione peroxidases (GPX), thioredoxin reductases (TrxR), selenoprotein P (SELENOP) and selenoprotein S (SELENOS). Selenium provides protection from pre-eclampsia through the functions of these selenoproteins. These selenoproteins protect against oxidative stress and inflammation. Inadequate selenium status may also contribute to the hypertension seen in pre-eclampsia.

When considering the effect of selenium supplementation in populations, it is important to consider their selenium status. In European countries including the UK, selenium status has been shown to be suboptimal. Conversely, baseline selenium intake of those in the US is higher, resulting in adequate selenium status.

Multiple studies have shown that the selenium status of women with pre-eclampsia is significantly lower than that observed in their normotensive counterparts. However, this effect has not been observed within the Boston Birth Cohort, likely due to the fact that American populations are selenium replete.

Furthermore, studies show that selenium supplementation is effective in reducing pre-eclampsia risk in women of inadequate selenium status. For example, a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial conducted by Rayman et al. found that supplementing primiparous women (women who are pregnant for the first time) with 60 µg selenium per day for 35 weeks was significantly associated with a reduction in pre-eclampsia risk.

Women with low selenium status should try to increase their intake of selenium containing foods, ideally by consuming more than two fish/seafood portions per week. Plant-based sources of selenium include brown rice, pasta and seeded bread, green and brown lentils, chia seeds, flax seeds, nuts and mushrooms and Brussel sprouts. However, all these foods contain a varying amount of selenium. Alternatively, women could take a pregnancy supplement containing 50-100 µg selenium as soon as they know they are pregnant and preferably when planning pregnancy.

Folic acid, vitamin B12 and multivitamins/minerals

Sufficient dietary intake of folate (supplemented as folic acid) during pregnancy is important for normal placentation, the growth and development of the foetus, and to prevent neural tube defects. Folate may play a protective role in pre-eclampsia as it is involved in mechanisms that lower blood pressure, reduce oxidative stress and restore endothelial function.

Multivitamins/minerals, which generally contain folic acid and vitamin B12, may also reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia through the protective mechanisms of the individual nutrients, some of which may work in synergy.

A prospective cohort study conducted by Vanderlelie et al. found that women who took a multivitamin/mineral preparation during the first trimester of pregnancy had a 67% reduced risk of developing pre-eclampsia. However, this effect was not significant in those with a BMI <25 kg/m2.

Moreover, a meta-analysis revealed that taking a periconceptual (around the time of conception) multivitamin or multivitamin/mineral supplement containing folic acid significantly reduces risk of pre-eclampsia but that folic acid supplementation alone does not.

To reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia, women planning to become pregnant should take a daily multivitamin/mineral supplement containing folic acid (400 µg) and vitamin D (≥10 µg), and in countries with low selenium status, selenium. If pregnancy is unplanned, such a supplement should start as soon as possible in pregnancy; this should be taken for at least the first trimester.

Related MyNutriWeb Content

Preconception and pregnancy nutrition and health – Early life nutrition masterclass (2022). Full day symposium in collaboration with Kings College London

Abi is my supervisor at HUTH and I am really pleased to be seeing this. Well done Abi you really deserve it 🙂