By Charlotte Radcliffe, Director & Registered Nutritionist at The Nutrition Consultant

The environmental impact of the food we eat is one of the key changes we can all make to tackle the issue of climate change. With up to 30% of GHG emissions globally being linked to agriculture and food production (1), and calls to government of the critical need to reduce consumption of dairy and meat*, focus has never been greater.

Consumers are listening and we have seen an exponential rise in the demand of plant-based alternatives, and subsequently the development and availability of them. The number of these products grew by almost 700% between 2015 and 2021, accounting for 12% of launches in 2021 (2).

As consumers continue to be aware of their diet’s environmental impact and more attuned to health concerns relating to the consumption of too much meat and dairy, the availability of plant-based products will continue to soar.

As health professionals, we can help guide consumers and food companies through the benefits associated with plant-rich diets and the nutrient differences of plant-based alternatives so they can be put into context of the overall diet.

(*The Climate Change Committee’s 6th Carbon budget recommendations to government stipulated the need to reduce consumption of dairy and meat by 20% by 2030 and a further 15% reduction in meat by 2050 if we are to achieve net carbon zero (3)).

In this blog, I’ll be:

- Exploring the nutritional composition of plant-based drinks and meat alternatives

- Sharing tips for advising clients on these products

- Providing recommendations for how the food industry can make positive changes to their product portfolio.

Plant-Based Drinks

The plant-based drinks category has substantially grown in popularity over recent years as many people choose to avoid or reduce dairy consumption as a result of the overall trend in plant-based diets; for animal welfare or allergy/intolerance reasons; and through increased availability.

They are often made from nuts such as almonds, cashews, and hazelnuts; legumes such as pea and soya; and cereals such as oat and rice. Some are also made from hemp seeds, coconuts and even potatoes!

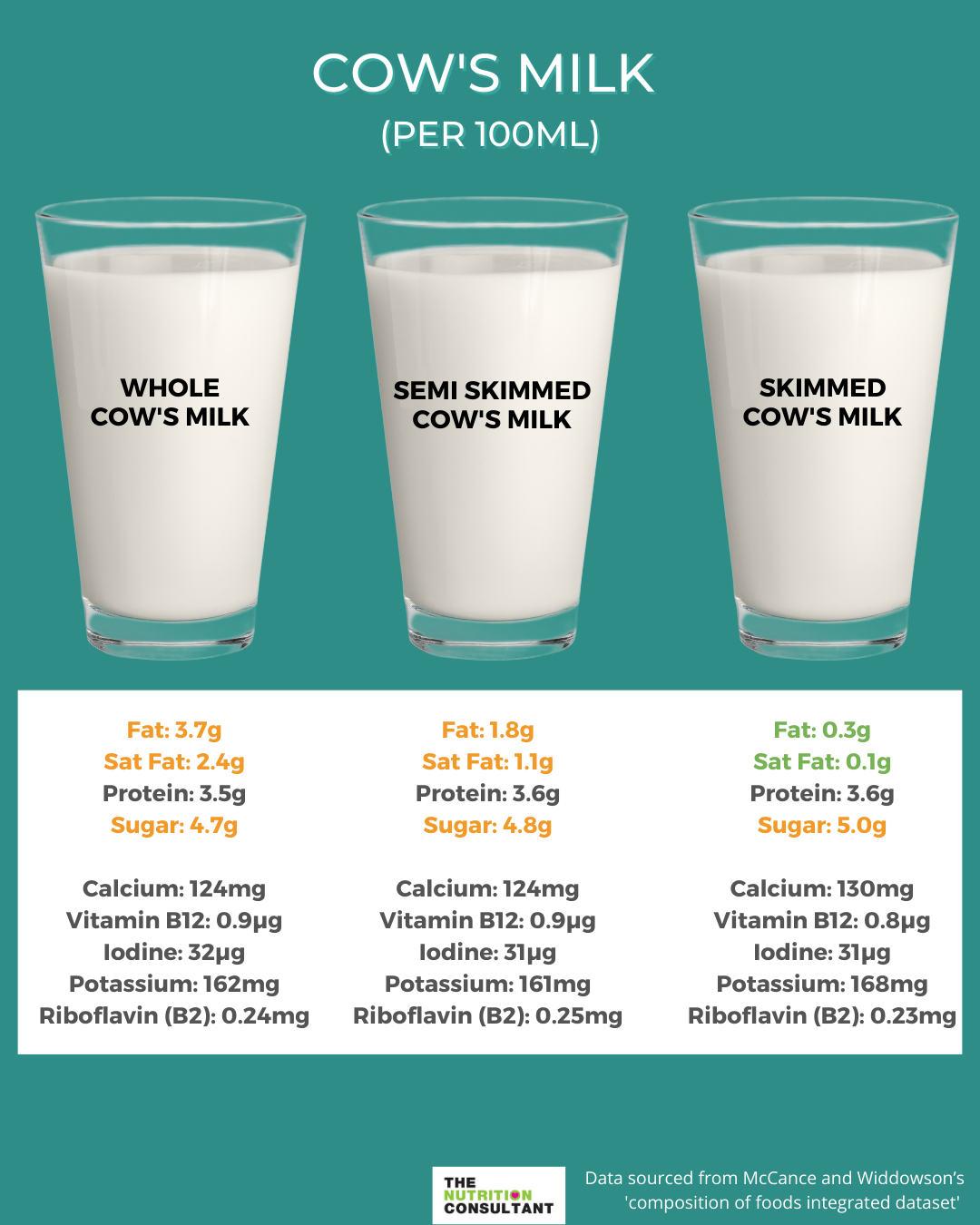

This section provides a snapshot of the nutritional composition of some of the main plant-based milk alternatives currently available in the UK. For comparison purposes though, let’s start with the nutritional composition of dairy milk.

Dairy Milk (cows)

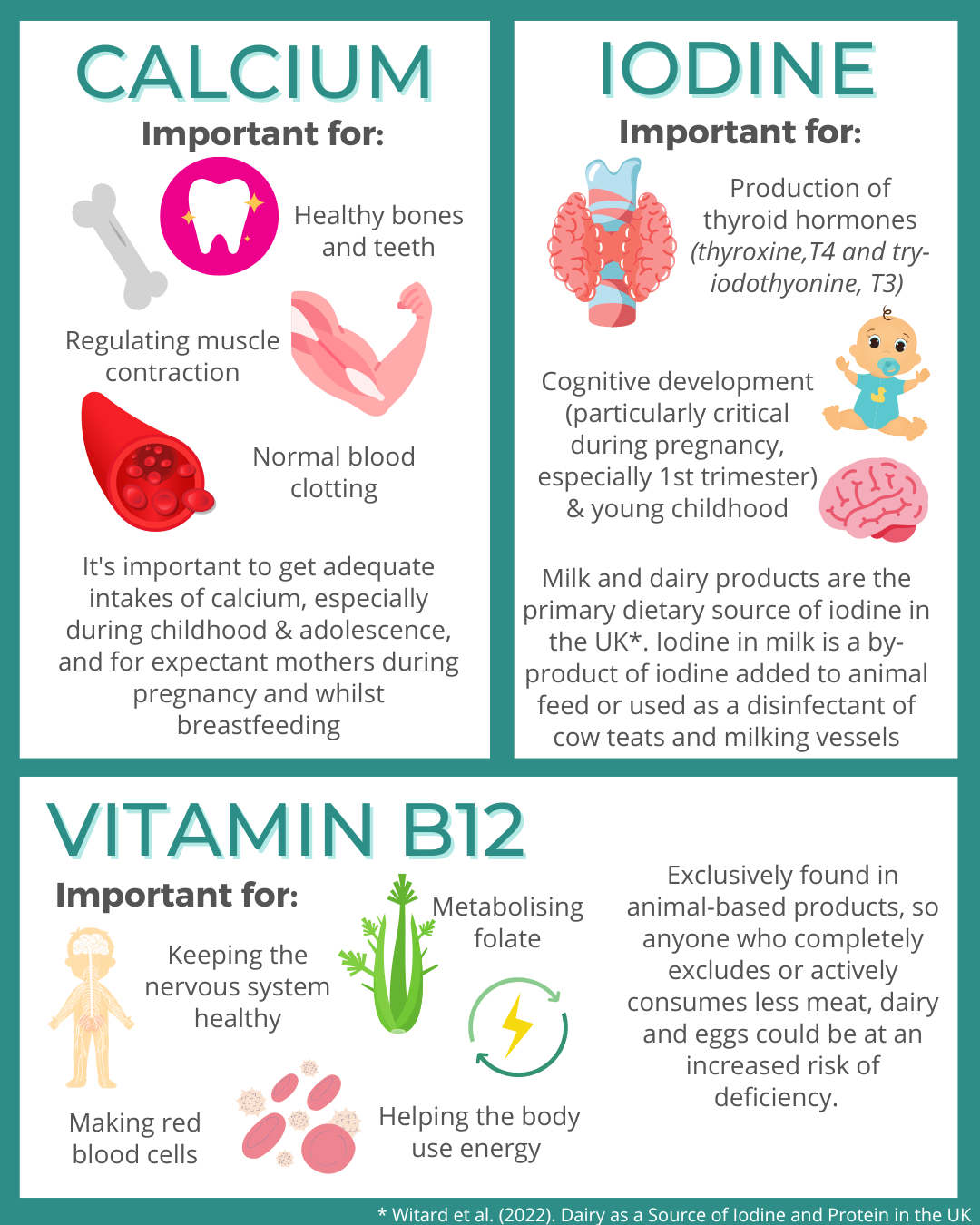

Cow’s milk is widely known for being a good source of calcium, but it also contributes towards daily vitamin B12 and iodine (if dairy cattle are fed iodine-fortified fodder or if used as a disinfectant of cow teats and milking vessels).

In addition to these 3 nutrients, cow’s milk contains other important micronutrients such as potassium and riboflavin (vitamin B2). Milk is also a source of complete protein, fat (including saturated fat), and is hydrating, all of which are important considerations when choosing a plant-based drink, especially for young children.

Nutritional Composition of Plant-Based Drinks

There is a vast variability in the nutritional composition of plant-based drinks depending on the ingredient base, and whether they are fortified. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of standardisation with micronutrient fortification and ‘Organic Food Regulations’ prohibit the fortification of organic variants.

Soya drinks are most comparable to dairy with regards to protein quantity and quality; other ingredient bases provide very little protein. However, as dairy milk should not be relied on as a key protein source for healthy adult population groups, there is little physiological relevance of the presence or absence of protein in plant-based drinks (this may not be the case for children under the age of 2 years).

Many, but not all, non-organic plant-based drinks are fortified with calcium and vitamins B12 and D. Some brands also fortify with vitamin B2, and a handful are beginning to fortify with iodine.

Vitamin D is often highlighted as a key dairy nutrient, however, unlike countries such as Canada where milk is mandatorily fortified with vitamin D, UK dairy does not provide any vitamin D, except for some products which may be fortified. The frequent fortification of plant-based drinks with vitamin D is there to further enhance calcium absorption.

The following infographic (click to download PDF) shows a selection of plant-based milk alternatives available currently in the marketplace, along with the accompanying nutritional composition (4). Fat, saturated fat and sugar have been colour-coded using the traffic light labelling criteria (5) (salt has been omitted due to low levels in this category).

Key Highlights:

Macronutrients

Overall, plant-based drinks are lower in energy, and except for soya, lower in protein, compared with dairy milk. Most are low in saturated fat, except for coconut drinks (and other drinks where coconut is added). Rice and oat drinks tend to be higher in energy.

The lower protein content although often highlighted, has little if any relevance to a healthy general adult population for a variety of reasons. Firstly, protein overconsumption is common, and omitting the small contribution from dairy could help align protein intakes with recommendations. Secondly, dairy milk and alternatives should not be relied on for protein, their key place in the Eatwell Guide is for the provision of calcium and there is a vast array of protein foods providing a significantly greater protein density than dairy or alternatives. Finally, with regards to protein quality and provision of essential amino acids, it is important we move away from focusing on individual foods and instead put foods in context of overall normal dietary consumption. It is well established that nitrogen balance occurs over the course of a day and is not dependent on one food, or one meal occasion, as most individuals consume a variety of foods with varying amino acid profiles over the course of a day. Providing energy and protein requirements are met, this will result in nitrogen balance, irrespective of the presence or absence of dairy or plant-based drinks.

For vulnerable groups, where protein needs to be maximised, soya drinks can be used alongside the inclusion of other rich protein foods, and supplementation is common irrespective of dairy or plant-based intakes.

Most plant-based drinks in the UK come in both sweetened and unsweetened varieties. Sugar is typically low throughout all the different ingredient bases and whether they contain added sugars or not. Usual levels are below 5g per 100ml. There are some exceptions such as oat and rice, where the majority of ‘sugars’ are because of the production process in which some of the starch from the grains are broken down into free sugars. As free sugars are cariogenic, unlike dairy lactose, unsweetened variants should always be considered and especially for children (particularly important for children under 2 years who tend to consume a greater volume of milk than older children or adults (6)).

Micronutrients

It is important for consumers to check the labels for fortification as it varies between brands and between ingredient bases. Additionally, organic variants are prohibited by law to fortify with micronutrients. For non-organic variants, fortification with calcium, vitamin B12, vitamin B2, and vitamin D is fairly standard.

A handful of plant-based drinks are beginning to include iodine, but this is not the norm overall.

Ingredients

Like dairy milk, water is the main ingredient in plant-based drinks with the plant solid making up anything from 2-10% of the end product.

Various plants are used as a base, legumes such as soya and pea, cereals such as oat and rice, nuts such as coconut, cashew and hazelnut.

Commonly used processing ingredients are added for a number of reasons. For example, stabilisers are often used to help thicken the liquid and help with texture; Emulsifiers help with shelf life and product consistency (especially keeping water and oil from nuts blended together); and flavourings are often added to intensify the flavour of the raw material.

Processing

All plant-based milks are currently classified as ‘ultra-processed’ foods (according to the NOVA classification criteria (7)) as they rely on added ingredients to enhance the sensory elements / improve shelf life as well as fortification with micronutrients. However, classifying foods purely by the degree of processing or ingredients, and without considering their nutritional profile has far reaching consequences (8, 9).

The NOVA system can also give mixed messages to consumers where pure animal fat such as lard or beef dripping, and coconut fats are considered better for health compared to vegetable spreads.

Advising Clients on Plant-Based Drinks:

If you work with clients (or parents of children) who include plant-based drinks, follow a plant-based diet, or have a dairy allergy or intolerance, there are some important points to consider when recommending a plant-based milk alternative:

- Ensure they check the nutrition labels to select plant-based drinks that have been fortified with micronutrients which dairy significantly contributes to in the UK diet i.e., calcium, iodine, and vitamins B12 and B2. Iodine is a particular one to look out for as many options do not include this currently.

- Make them aware that organic variants cannot be fortified with micronutrients by law, and you should guide them to other significant sources.

- For iodine, if fish (especially white) and dairy is not being consumed at all, supplements should be considered, but at no more than 150mcg per day for adults. For children this will be lower and should be discussed with a health professional.

- Vitamin B12. There should be no problem if the diet contains other dairy, meat, and eggs. However, if a vegan diet is being followed, three to four daily servings of vitamin B12 fortified foods and / or a vitamin B12 supplement should be considered.

- Calcium is ubiquitous in the diet, and there are many other sources that can be encouraged such as nuts, seeds, fish with soft bones, flour-based products, low oxalate green veg such as pak choi, kale and lady’s fingers.

- The protein quantity and quality of plant-based drinks is not relevant for most of the general adult population (and older children and teenagers) consuming a mixed diet and achieving their protein and energy requirements, which is the vast majority. This is not surprising with the plethora of protein dense food options. Only in special circumstances should dairy be seen as a significant source of protein in the diet and in these situations, individuals should be receiving specialised dietary advice. Soya and pea-based plant-based drinks, will provide protein comparable to dairy milk.

- Parents can introduce fortified unsweetened plant-based drinks as a main drink source after 12 months (same as cow’s milk). Children after the age of 1, should be consuming a mixed and varied diet with food from the Eatwell Guide protein group being the main contributors to their overall protein intakes.

- Rice milk is not recommended to children under the age of 5 due to the arsenic content.

- Choose unsweetened / no-sugar versions to minimise free sugar intake.

- Oat and rice drinks can be high in free sugars, whether sugar has been added or not (when the drink is processed, some of the starch is broken down into free sugars). This is important to consider if giving to a young child as they tend to consume a greater volume of milk than older children or adults. Some manufacturers are now modifying their production processes and there are ‘zero sugars’ varieties available.

Although plant-based yogurts or cheeses haven’t been included in this blog, here is a summary of what to look out for:

Plant-Based Cheese Alternatives

- Like dairy cheese, most cheese alternatives can be very high in salt, and most are low in protein. A typical cheddar cheese made with dairy has around 25g of protein per 100g, whereas most plant-based alternatives have between 0-2g of protein per 100g.

- Most are high in saturated fat, often because they have added coconut and / or palm oil.

- Look out for ones that are fortified with calcium, vitamin B12 and vitamin D.

- Like dairy cheese, keep portions small and consume less frequently.

Plant-Based Alternatives to Yogurt

- Similar advice to the plant-based drinks, although iodine fortification is even harder to find in plant-based alternatives to yogurts.

- Soya-based varieties are ideal for vulnerable groups due to their higher protein content.

Plant-Based Meat Alternatives

According to the 6th Carbon budget a 20% reduction in meat by 2030 and a further 15% reduction by 2050 is critical if we are to reach net carbon zero (3). This reduction is far more lenient compared to the over 50% reduction in red meat as recommended by the EAT-Lancet commission (10)

From Greggs sausage rolls to Beyond Meat, there has been a huge growth in the availability of plant-based meat alternatives in recent years. This abundance of convenient and tasty meat alternatives makes it unsurprising that more and more people are going meat-free or reducing their meat consumption.

This section provides a snapshot of the nutritional composition of some of the main plant-based meat alternatives currently available in the UK. The nutritional profile varies greatly, and it is important to consider how nutritionally balanced these options are.

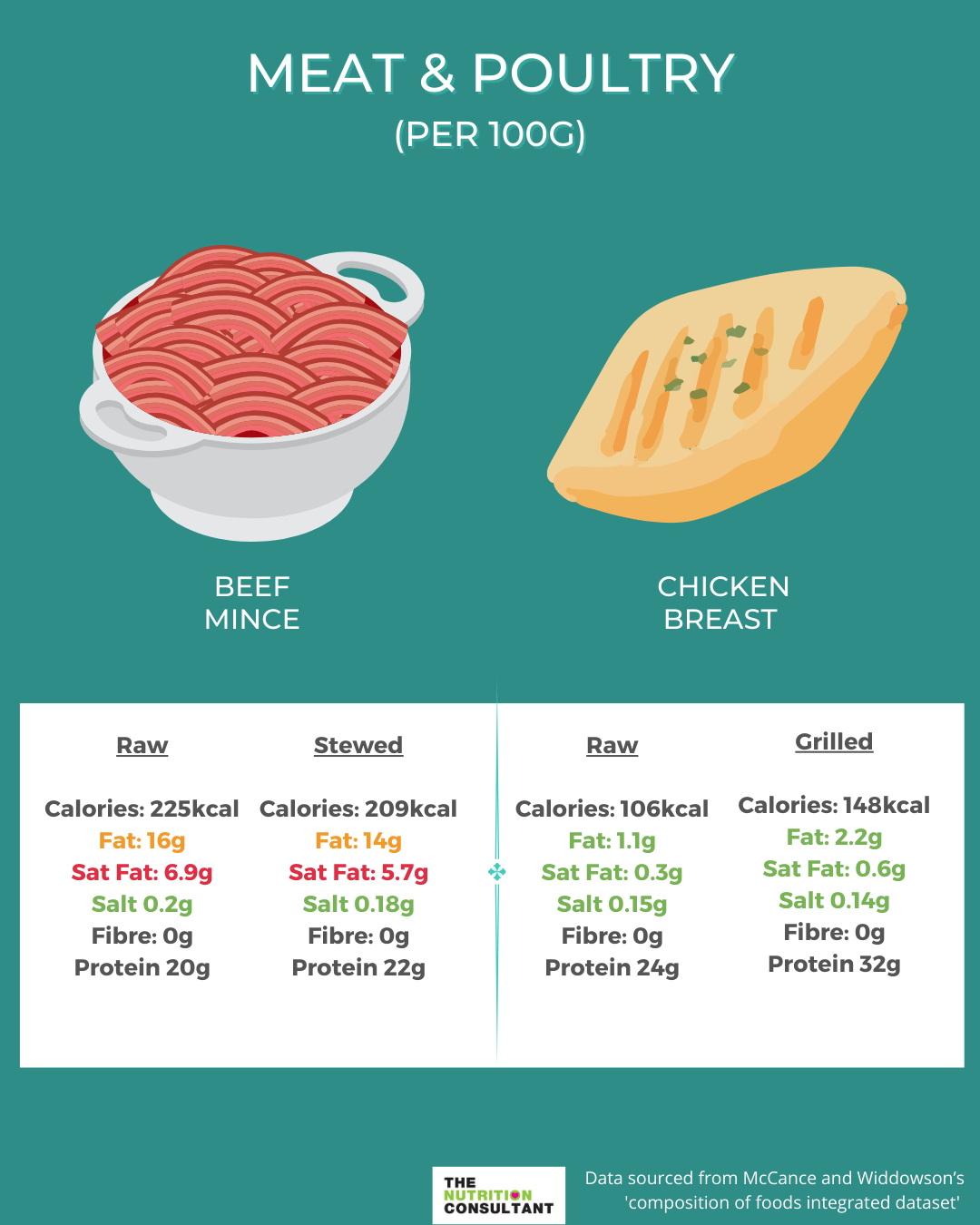

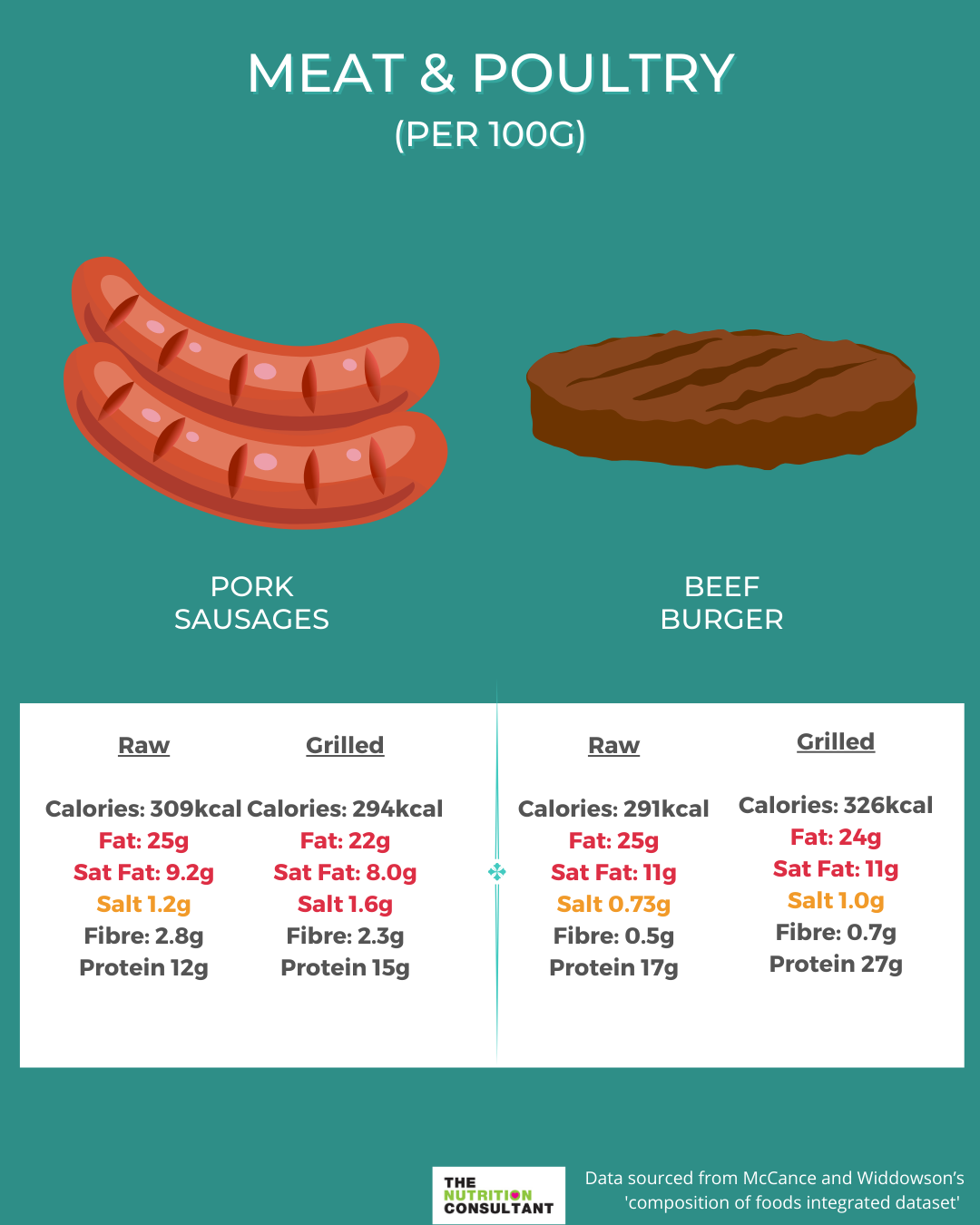

For comparison purposes, let’s start with the nutritional composition of meat and poultry.

Meat & Poultry

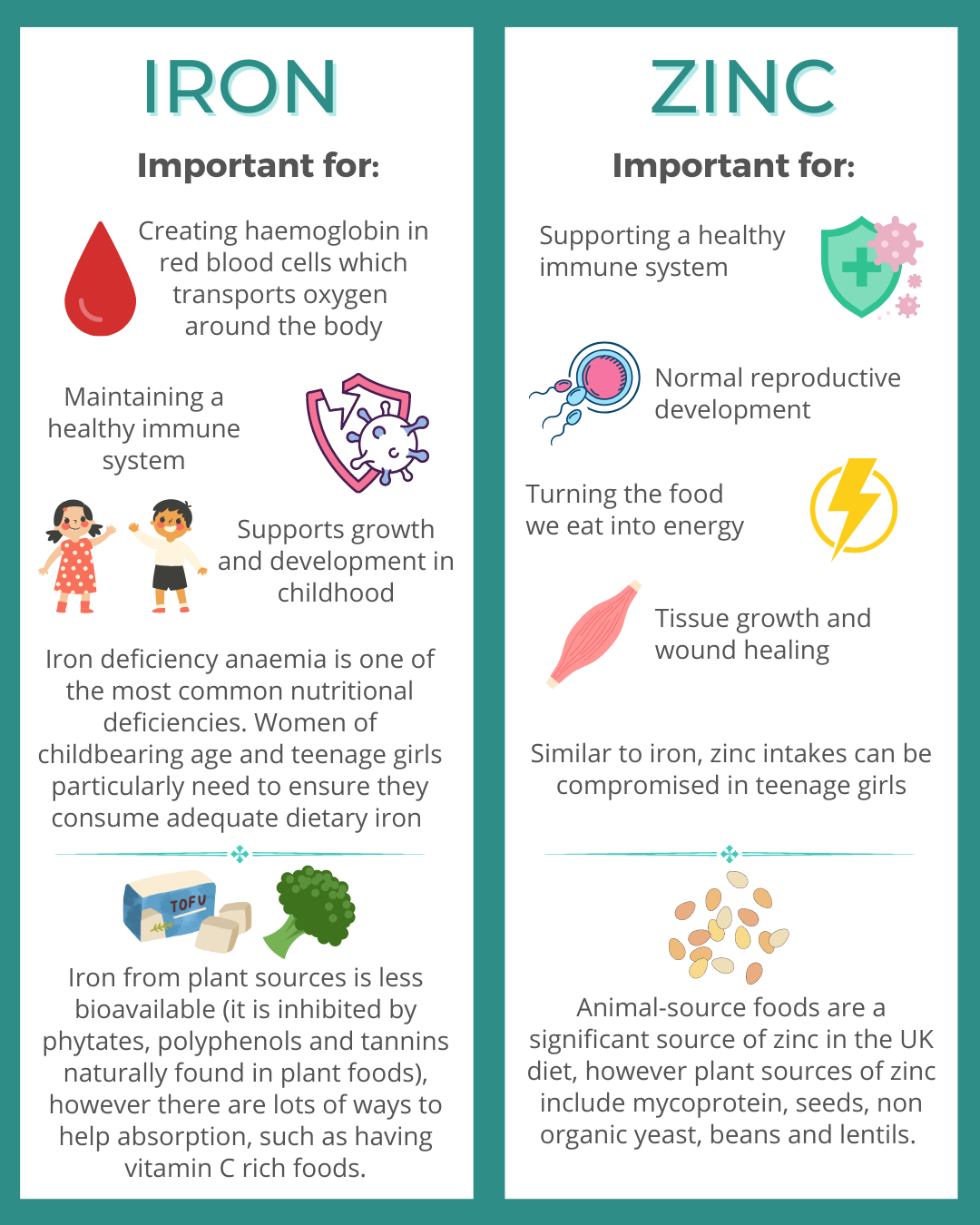

Meat is also typically a good source of protein, iron, vitamin B12, and zinc. I have already discussed the importance of vitamin B12, and below you’ll find a snapshot summary of why the other nutrients are also important.

The following infographic (click to download PDF) show a selection of plant-based meat alternatives along with the accompanying nutritional composition (4). Fat, saturated fat and salt has been colour-coded using the traffic light labelling criteria (5) (sugar has been omitted due to low levels).

Key Highlights:

Macronutrients

- Overall, plant-based meat alternatives tend to have lower amounts of saturated fat than meat products. This is especially the case for plain mycoprotein, soya mince / pieces or TVP and tofu.

- However, some processed meat alternatives, such as burgers, sausages, and ready meals, can be high in saturated fats due to the addition of coconut and / or palm oil for organoleptic qualities and labels should be checked.

- Salt content is generally higher in plant-based alternatives versus meat equivalents, however, seasoning of salt during or after cooking of meat should also be considered (nutritional composition data doesn’t take this into account).

- Protein content can be lower than the meat equivalent. This is fine for those achieving their daily calorie needs and eating a wide variety, but it is important to be mindful of this for people who have higher protein requirements.

- Some brands add iron and vitamin B12 to their recipes, and they are also present in products which use wheat flour (which has to be fortified by law).

- Generally, plant-based meat substitutes contain significantly more fibre than their meat equivalents due to their natural composition (e.g. soya based products and mycoprotein (Quorn)), or through the presence of added carbohydrate in the formulation.

Ingredients

Plant-based meat alternatives are typically made up of soya, wheat, pea or mycoprotein (or a mix of these).

Sometimes colouring is used to mimic the appearance of meat, and oils are often added to aid texture, flavour and juiciness. Usually they contain binding ingredients, such as egg whites (in non-vegan options) or methyl cellulose (vegan options). Coconut oil is often used in burger-type burgers as this helps produce a texture similar to animal fat (11).

Processing

Most mock meats are classed as ‘ultra-processed’, whereas only meat-based sausages and other reconstructed meat / fish products would fall under the category of ‘ultra-processed’.

Similar to plant-based drinks alternatives and meat products, the overall nutritional profile needs to be considered. Consumers should be advised to seek out the varieties with a healthier profile. Indeed, this is easier for consumers to assess as plant-based alternatives often provide front of pack traffic light labelling.

Advising Clients on Plant-Based Meat Alternatives:

If you work with clients who follow a vegan or vegetarian diet, or anyone who is trying to reduce their meat consumption, here are some important points to consider when choosing plant-based meat alternatives:

- Use plain mycoprotein, soya mince / pieces and tofu wherever possible, in place of the more processed products such as burgers, sausages, pies, ready meals etc.

- For processed meat alternatives – check the nutrition labels especially for saturated fat and salt.

- The salt content of some meat processed replacement products can be at the higher end, so it’s important to emphasise why these should be eaten in moderation and that opting for lower salt options (e.g. plain tofu / tempeh) where possible will help reduce salt intake.

- Products that contain coconut and / or palm oil are typically high in saturated fat.

- The majority provide adequate protein and will be suitable for the general population consuming a mixed diet and achieving their protein and energy requirements (which is the vast majority).

- Opting for meat alternatives that are fortified with vitamin B12 and iron will help ensure key nutrients are replaced when omitting meat from the diet (however supplementation may also be required).

- Compared to highly processed meat alternatives, whole food sources of plant-based protein such as beans, lentils, chickpeas, nuts and seeds or less processed products (such as tofu / tempeh), plain mycoprotein, soya mince/pieces etc., are comparable to meat for protein and are higher in fibre and lower in saturated fat and salt.

Recommendations for the Food Industry

As nutrition professionals, we have the power to collaborate with the food industry and influence positive changes to their nutrition strategies and product portfolio. Given the increasing popularity of plant-based alternatives, there is a huge opportunity to make a meaningful impact on the nation’s health, and the health of our planet, through reformulation or new product development.

Here are some of my recommendations for nutrition professionals working in the food industry:

- Work with food development teams to create new products with minimally processed plant-based proteins and make use of whole foods such as legumes, nuts and seeds. Try and prioritise the development of plant-based alternatives that will have the biggest environmental impact (such as beef substitutes). Where possible, plant-based sources should be diversified, and protein quality should be a key consideration, especially for children and older people.

- Consider how the nutrition of a product can be improved to reflect what people are replacing it for. For meat alternatives, ensure sufficient iron, protein, and vitamin B12. For milk alternatives, fortify with calcium, vitamin D, iodine, and vitamin B12. Aim to maintain similar protein levels to dairy where possible.

- Set nutritional thresholds to limit the amount of salt and saturated fat added to products and find alternative ways to mimic the flavour and texture of meat. Ideally, the plant- based alternative should be nutritionally superior to the animal-based version. Consumers are demanding not just plant alternatives, but healthier plant alternatives!

- Be aware of the legalities of naming plant-based products. For example, plant-based drinks cannot use the term ‘milk’ as this term is protected under EU legislation for use on animal products only (Council Regulation EU 1308/2013 (12)), hence the phrases ‘milk alternative’, ‘m’lk’, ‘mylk drink’ or similar being used across these products. It is also important to keep up to date with changes to legislation. Although a recent EU proposal (Amendment 171 (13)) to ban marketing terminology such as ’creamy texture’ on plant-based alternatives was not taken forward, stricter rules in the UK are in their preliminary stages. If it proceeds, companies would not be able to use descriptors such as ‘milk alternative’, ‘mylk’ or ‘not milk’; use marketing imagery that evokes milk; or use brand names which use these descriptors in e.g. M.L.K.Ology.

- Allergens risks should also be integrated into menu decisions, especially as plant-based products may still contain ingredients such as milk or egg, or be produced in factories where these ingredients are used in other products (potential cross contamination). Consumers might not automatically realise this.

- Consumers often believe the presence of plant ingredients is a healthier way of eating, but as this isn’t always the case, contextualizing and communicating the format of the plant-based alternative is important e.g. avoiding any ‘health halo’ marketing unless it is warranted. This goes along with supporting positive communication around plant-based alternatives, especially around wholefood plant-based ingredients.

- Communication and education of plant-based diets needs to be improved across the population – both in terms of the important nutrients which might be lacking, fortification where relevant, and educating on the importance of diversity of diets (e.g. 30 plants a week). Businesses can help do this.

- Stay close to industry development around lab grown meat and dairy. These potentially will play a big part of our food supply in years to come.

- The future success of plant-based meats and drinks depends on ensuring nutrition and environmental impacts are assessed equally, along with great taste and value.

Summary

There is scientific consensus that prioritising plants in the diet can lead to better outcomes for the health of people and the planet, however, as with animal-based diets, plant-based diets need to be well planned to meet dietary needs.

- The international and national advice for environmentally sustainable diets is to reduce current meat intakes. There is no guidance to remove meat or dairy from diets, but if advising clients with specific dietary preferences or allergies/intolerances which means that they do not eat dairy or meat-based products, it’s important to consider the nutrients they might be lacking in their diet and how to replace these.

- Opting for plant-based drinks that are fortified with calcium, vitamin B12, iodine, and vitamin D can reduce the risk of deficiencies. For vulnerable groups who may be more reliant on dairy as a protein source (e.g., under 1 year olds) it is also important to consider drinks that are similar in protein content such as those based on soya and pea.

- Removing meat completely from the diet requires the addition of vitamin B12 fortified alternatives and / or supplementation and advice on other rich food sources of iron and zinc should be given.

- The plant-based industry is growing at a rapid rate, with the number of new plant-based packaged goods increasing exponentially.

- The nutritional profile of meat alternatives varies significantly, but overall, they are lower in saturated fat (unless containing coconut and/or palm oil) and higher in fibre. However, the salt content is often at the higher end (with an amber or red traffic light label) and the protein content of some alternatives can be lower in comparison to meat (although this is not significant of clients are achieving their daily calorie needs and are eating a variety of foods).

- There are many opportunities for nutrition professionals to collaborate with the food industry to make an environmental or health-promoting impact with plant-based alternatives, either through reformulation or new product development strategies.

- Populations haven’t always consumed meat and dairy and we know a lot about whole foods and plant-based diets overall. But there is a lot we don’t know about alternative products – we don’t know the long-term impacts (if any) of some of the newer / more novel ingredients. More research is needed.

- Whole-food plant-based proteins such as legumes, soya beans, nuts and seeds are more nutritious and offer more health benefits than the highly processed meat alternatives currently on the market. They provide a range of nutrients and are good sources of fibre. However, meat alternatives are a convenient replacement for meat and can form part of a balanced diet along with more nutritious whole sources of plant protein, but variety is key.

References

- British Dietetic Association One Blue Dot Resources. https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/one-blue-dot.html

- Mintel (2023). Emerging Trends in the Plant-Based Industry. https://www.mintel.com/food-and-drink-market-news/emerging-plant-based-trends/

- The Sixth Carbon Budget: The UK’s Path to Net Zero. December 2020. https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-Sixth-Carbon-Budget-The-UKs-path-to-Net-Zero.pdf

- Product nutrition information sourced from Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s, Waitrose, and Ocado.

- Guide to creating a front of pack (FOP) nutrition label for pre-packed products sold through retail outlets. https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/fop-guidance_0.pdf

- First Steps Nutrition Trust: Plant-based milk alternatives in the diets of 1–4 year-olds. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59f75004f09ca48694070f3b/t/609250486fead72b89e9de8d/1620201544784/Plant+based+milk+alternatives+in+the+diets+of+1-4+year+olds_April2021a.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2019) Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system. https://www.fao.org/3/ca5644en/ca5644en.pdf

- British Nutrition Foundation Position Statement on Ultra Processed Foods. https://www.nutrition.org.uk/media/swdophda/upf-position-statement-april-2023.pdf

- British Dietetic Association Position Statement on Processed Foods. https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/processed-food.html

- Eat_lancet Comission. Summary Report 2019. https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2019/07/EAT-Lancet_Commission_Summary_Report.pdf

- An investigation of the formulation and nutritional composition of modern meat analogue products. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2019;8(4):320-9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213453019301144

- Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 17 December 2013. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:347:0671:0854:EN:PDF

- EU Amendment 171. https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2021/05/26/Europe-drops-Amendment-171-allowing-for-creamy-and-buttery-plant-based-dairy#

Hi, this was a very interesting read, thank you. I would like to ask about the by products of production of the non-meat alternatives. The reasons for eating less meat are based around carbon emmissions. However, where do we stand on water usage and electricity consumptions for example with their “replacement” and their production effects on the environment and soil. A direct comparison would be very interesting. There is also the argument that grass fed meat has a positive impact on the soil/ground that they graze/tread and some ecosystems. Non meat products may also need fertalisers and pestacides, like wise, meat may have been treated with anitbiotics.

I feel this is a very complicated area. And fortification may make the products more nutrient compariable but are they any better for the environment as a whole.

Thank you for taking the time to read my comment.